Wadi al-Shatii: Struggles Along the Road

Introduction

In 2023, a delegation from the Government of National Unity’s Roads and Bridges Department visited areas around the town of Brak, in the Wadi al-Shatii district in southwestern Libya, to inspect projects under implementation. Concurrently, Deputy Prime Minister Ramadan Abu Janah also met with a delegation of representatives from the southern region to discuss the needs of residents and the difficulties experienced in the region.[1] However, these initiatives have yet to enhance the region’s overall conditions. This policy brief examines the deteriorating roads in Wadi al-Shatii, using it as a case study to highlight the shortcomings of the local administrative system and its broader impact on public services.

Background on the Wadi al-Shatii district

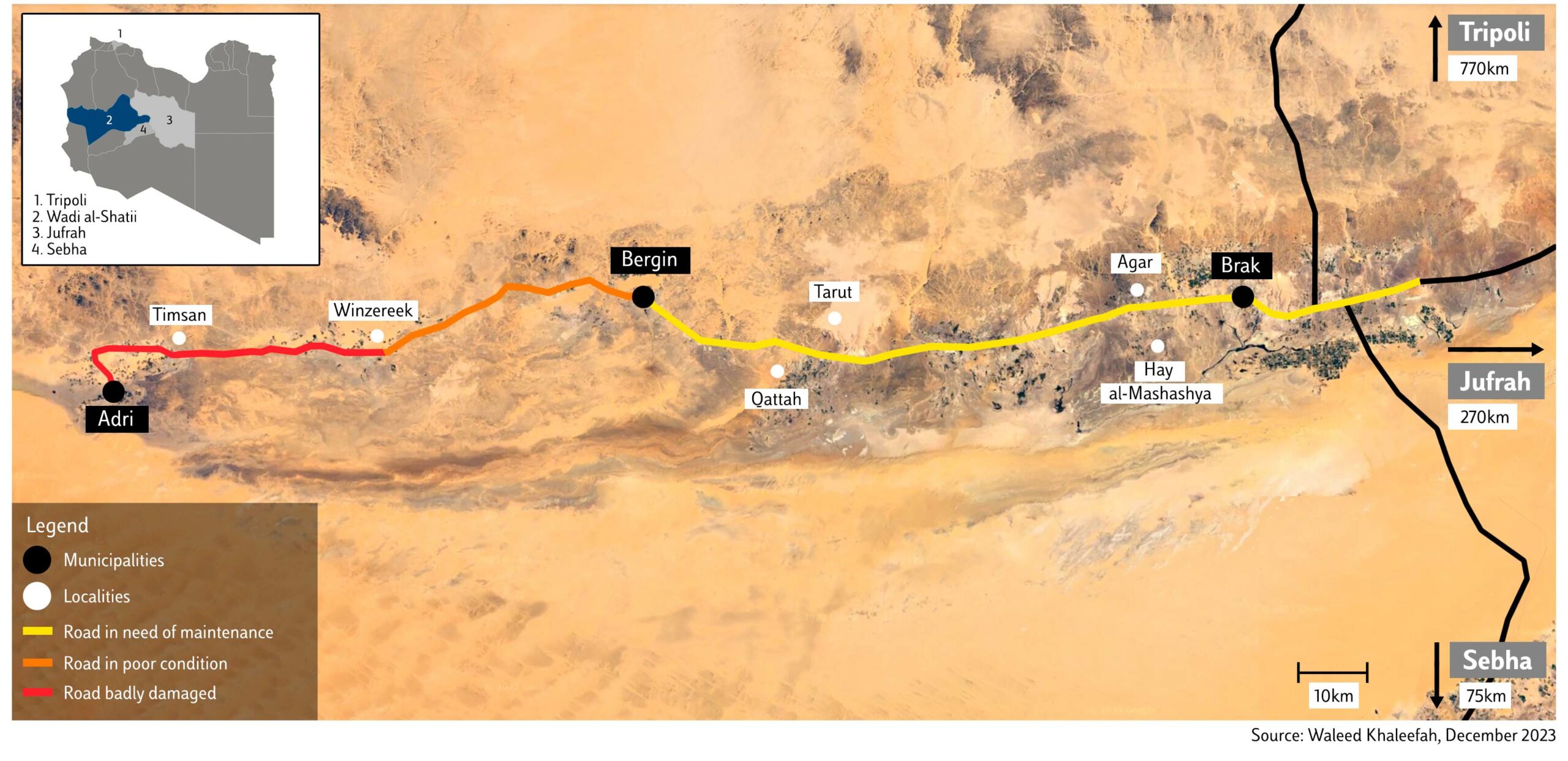

The Wadi al-Shatii district is strategically located as a gateway to Libya’s southwestern Fezzan region. It is a geographical band that extends a 170 km westward stretch, overlooking the Sebha – Tripoli Road. The district is situated 710 km south of the capital city of Tripoli, and 75 km north of the southern capital of Sebha. Its population ranges from 80,000-90,000 people, most of whom work in agriculture and cattle farming.[2] The region is renowned for its diverse natural resources, including, water, marble, sand, and iron.[3] Its strategic location and resource wealth positions it as a potential hub for development, investment, and as a logistical nexus connecting northern and southern Libya, with prospects for various mining industries.[4]

Over the past decades, residents of the Wadi al-Shatii district endured poor public services as a result of governmental delays in implementing development plans.[5] Since 2011, the district, particularly its western part, has seen a marked decline in services, due to security instability, political division, and changing governments.[6] Schools in the area grapple with inadequate infrastructure, lacking basic furniture and suitable playgrounds, while their walls are in complete disrepair.[7] In the healthcare sector, most medical centers face critical shortages of basic supplies and medicines, including vital treatments such as scorpion antivenom.[8] Similarly, the banking sector suffers from poor services, such as providing financial liquidity, facilitating money transfers and withdrawals, and processing checks.[9]

Beyond the deficiencies in public services, Wadi al-Shatii’s road network has been noticeably neglected since the 1990s. To this day, the region relies on a single main road extending 170 km, which is inadequate for the growing population. The road in the western part of Wadi al-Shatii lacks essential features like road signs and gas stations. Its deterioration, marked by increasing cracks and potholes, is due to delayed maintenance and substandard repair work, which does not conform to road specifications. Additionally, some sections of the road, like the 15 km stretch between Adri and Timsan, remain unpaved, adding to the region’s transportation challenges.[10]

Resident encroachments and a general lack of legal awareness further exacerbated the road’s degradation. Heavy trucks frequently exceed the legal weight limit of 60 tons, compounding the road damage beyond what normal vehicle loads could cause.[11] In addition, many residents encroach upon the road’s right of way, with some constructing buildings near it. Others deliberately damage the pavement to slow down traffic or dig deeper to install utilities like power or water lines for their homes or workplaces, without restoring the road to its original condition. These activities have led to severe deterioration, leaving parts of the road in crumbles to the point of collapse.[12]

How roads affect the daily lives of residents

Residents in Wadi al-Shatii face various challenges and hazards stemming from poor road conditions. These include armed robberies by bandits targeting motorists. [13] In other cases, many drivers, especially at night, lose their way due to the absence of road signs, leading to increased accidents.[14] In the western part of the valley, pregnant women are particularly vulnerable, as the only available route is an unpaved road full of potholes and bumps,[15] heightening the risk of miscarriage during travel. Moreover, accessing medical centers is a challenge for women, with the nearest facility located 60 km east, resulting in prolonged and arduous journeys.

Economically, the condition of the roads in Wadi al-Shatii’s western part have significantly impacted local residents. Rising shipping costs over the past few years have led increased prices of goods and essentials. The road conditions also contribute to a higher consumption of auto parts, and therefore, higher vehicle maintenance expenses, negatively affecting the standard of living.[16] Socially, the transportation challenges have led some families to stop their children’s schooling, as many students are obliged to travel 5 km from between areas. Additionally, the travel difficulties have reduced social interactions, as residents find it hard to visit their friends and relatives in different areas.[17] These factors contribute collectively hinder access to public services, prompting some residents to relocate to areas with better services, thereby contributing to displacement and migration within the region.[18]

Figure 1: Map of Wadi al Shatii

Gaps in the local administrative structure

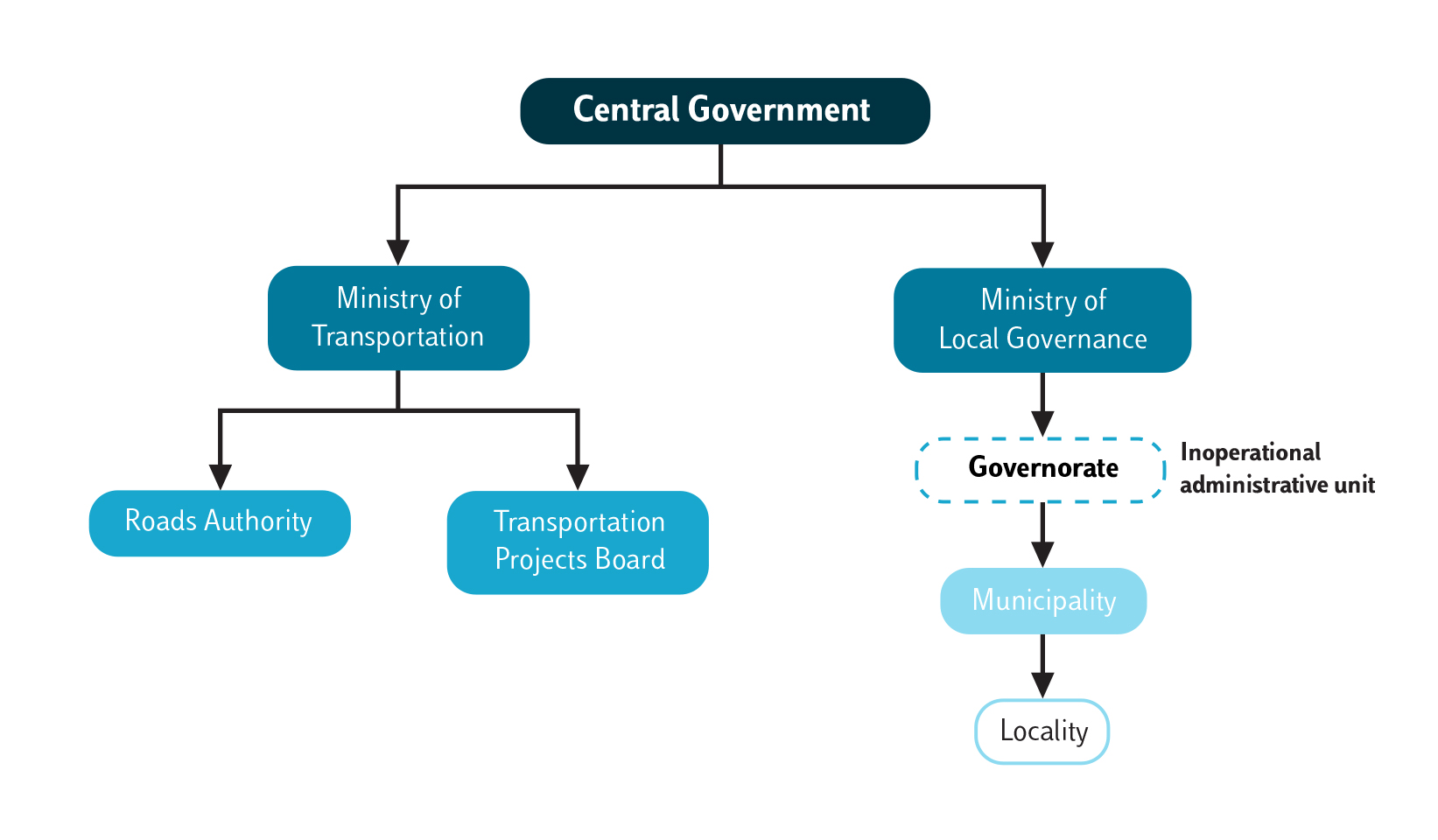

The local administrative system in Wadi al-Shatii faces significant challenges due to the incomplete implementation of Law No. 59, which sets the administrative structure. This has resulted in the existence of a quasi-centralised system instead of a more local, decentralised one. Ideally, the local administrative structure should consist of four levels: the Ministry of Local Governance, the Transportation Authority, the governorate, and the municipality, each with distinct roles in road project execution. The Transportation Authority is responsible for planning and budgeting projects, while the Ministry of Local Governance provides government support. The governorate’s role is to monitor and oversee project implementation within municipalities. The municipalities, in turn, are tasked with managing local projects. However, the absence of a functional administrative unit at the governorate level creates a systemic gap. As a result, municipalities lack the necessary prerogatives, funding, and support to implement projects on the ground.

The disparity in public services across Libya is stark, with conditions in municipalities near the center faring better than those in more remote areas. A notable decline in service quality is observed as one moves away from the capital, Tripoli, particularly in southern municipalities that have endured decades of marginalisation and neglect. The constraints imposed by Law No. 59 on local administration, which only grants municipalities administrative prerogatives, exacerbates this issue. Lacking the authority to utilise local funds and resources, municipalities are unable to independently finance or manage projects. Furthermore, their inability to contract for or supervise ongoing projects—coupled with the government’s preference for allocating substantial funds to central agencies—further widens the service disparity between central and outlying regions.

Figure 2: Wadi al Shatii local governance structure

Government inefficiency and resident intervention

Local government, as represented by the municipality, is rendered ineffective in managing local affairs due to the systemic constraints mentioned above. This inefficiency is most apparent in the government’s inability to maintain existing roads, develop new ones, or even prevent encroachments on the right of way. A case in point is the lack of a dedicated road maintenance authority in Wadi al-Shatii. [19] Consequently, while new roads are constructed in areas closer to the center, remote regions suffer from a lack of road maintenance and development, failing to meet the needs of their residents. Despite the municipality’s efforts to communicate with the central government, the lack of a substantial response highlights issues in the communication and coordination mechanisms between the government and local municipalities.

The implementation of road projects has faced delays at every stage due to several difficulties. Initially, during the contracting stage, the government requires companies to undertake complex administrative procedures, including tax filings and approvals from regulatory authorities such as the Audit Bureau. In turn, companies often insist on upfront funding before commencing projects.[20] During the project implementation phase, the limited capabilities of local companies become evident, especially when contrasted with the project’s scale.[21] Delays often occur in essential tasks like compaction testing and soil analysis. Projects also encounter logistical challenges, such as the remoteness of mixing sites and ports, which slows the timely delivery of raw materials. Additionally financial obstacles, such as the high prices of raw materials and insufficient budget allocations for road and bridge projects in the southern region further impede projects.[22] These problems go back to the failure to grant the municipality the powers to supervise projects and evaluate the companies implementing the projects.[23]

At the same time, the government’s oversight in supervising the progress of road projects has been lacking. This includes projects initiated before 2011 that have yet to resume, and others that have faced delayed completion. Notably, both the Bergin-Adri road project, which was contracted in 2008, and the Qattah-Adri road project have been stalled since 2011. In contrast, the government’s focus seems to be on small-scale projects, such as painting, installing reflectors and protective fences for the Sabha-Brak road, and building entrances for towns like Tarut, Hayy al-Mashashia, and Agar. However, these efforts fall short in substantially enhancing road conditions or transportation for the residents of Wadi al-Shatii. Moreover, the government has not punished encroachments on the road or imposed penalties on trucks that exceed the 60-ton legal weight limit.

The government’s delay in implementing road projects has prompted residents to intervene to mitigate the deterioration of the roads. Since 2012, to improve the condition of sections of the Qattah-Adri road, the residents of Adri municipality have periodically resorted to filling potholes with animal skins and patching cracks using mud and oil residues.[24] Faced with the municipality’s limited capacity to address the situation, the residents submitted a proposal to construct alternative routes to the Ministry of Transportation. However, this has yet to yield any significant results.[25]

Conclusion

Given the current state of the road network in Wadi al-Shatii, there is a pressing need to address the deteriorating conditions, which are likely to worsen over time. Improved roads are crucial for enabling residents to access essential services, facilitating travel between municipalities, and enhancing social interaction. However, this requires navigating a range of administrative, financial, and logistical challenges, as well as issues related to tribalism and financial corruption.

First, a comprehensive plan is essential for maintaining existing roads and resuming stalled projects. The plan should include forming contracts with companies whose capabilities match the scale of these projects. Second, clarifying and assigning roles between the government and the municipality will be key for effective management, implementation, and supervision of the road projects. Finally, establishing a clear communication protocol is necessary, both between the central government and the municipality on the one hand, and between the residents and the municipality on the other, to ensure that all parties are aligned and informed.

Footnotes

[1] Al-Wasat, “Abu Janah discusses the needs of the South with a delegation of the region’s constituents”, 6 October 2021, https://alwasat.ly/news/libya/334949.

[2] Interview with President of Wadi al-Shatii University, telephone conversation, 19 April 2023, and interview with a resident of Mahrouqa area, telephone conversation, 19 April 2023.

[3] Interview with a political writer, telephone conversation, 4 May 2023.

[4] Interview with President of Wadi al-Shatii University, telephone conversation, 19 April 2023.

[5] Interview with a Professor of Pharmacy at Sebha University, telephone conversation, 1 May 2023.

[6] Interview with President of Wadi al-Shatii University, telephone conversation, 19 April 2023.

[7] Interview with a Professor of Pharmacy at Sebha University, telephone conversation, 1 May 2023.

[8] Interview with a resident of Mahrouqa area, telephone conversation, 19 April 2023.

[9] Interview with a resident of the Mansoura area, telephone conversation, 1 May 2023.

[10] Interview with a resident of the Winzereek area, telephone conversation, 17 June 2023.

[11] Interview with Director of the Roads and Bridges Department, Sabha Branch, telephone conversation, 19 June 2023.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Personal observation

[14] Interview with a resident of the Winzereek area, telephone conversation, 17 June 2023.

[15] Interview with Mayor of Adri, telephone conversation, 9 July 2023.

[16] Interview with a resident of the Winzereek area, telephone conversation, 17 June 2023.

[17] Interview with a resident of the Adri area, telephone conversation, 11 June 2023.

[18] Interview with Mayor of Adri, telephone conversation, 9 July 2023.

[19] Interview with Director of the Roads and Bridges Department, Sabha Branch, telephone conversation, 19 June 2023.

[20] Interview with a resident of the Winzereek area, telephone conversation, 17 June 2023.

[21] Interview with Director of the Roads and Bridges Department, Sabha Branch, telephone conversation, 19 June 2023.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Interview with a resident of the Adri area, telephone conversation, 11 June 2023.

[25] Ibid.

In Focus

Levels of Government and Administrative Boundaries in Libya’s Future Local Governance System

KHERIGI, Intissar

2 July 2025

The GCC States’ Security Policies in the Red Sea Geopolitical Border: Factors and Policy Options

ARDEMAGNI, Eleonora

26 June 2025

Sleepwalkers into War Are Algeria and Morocco on the Path to Conflict?

KHECHIB, Djallel

25 June 2025