Strategic Choices in the Sahel - A Vademecum for Italy

Introduction [1]

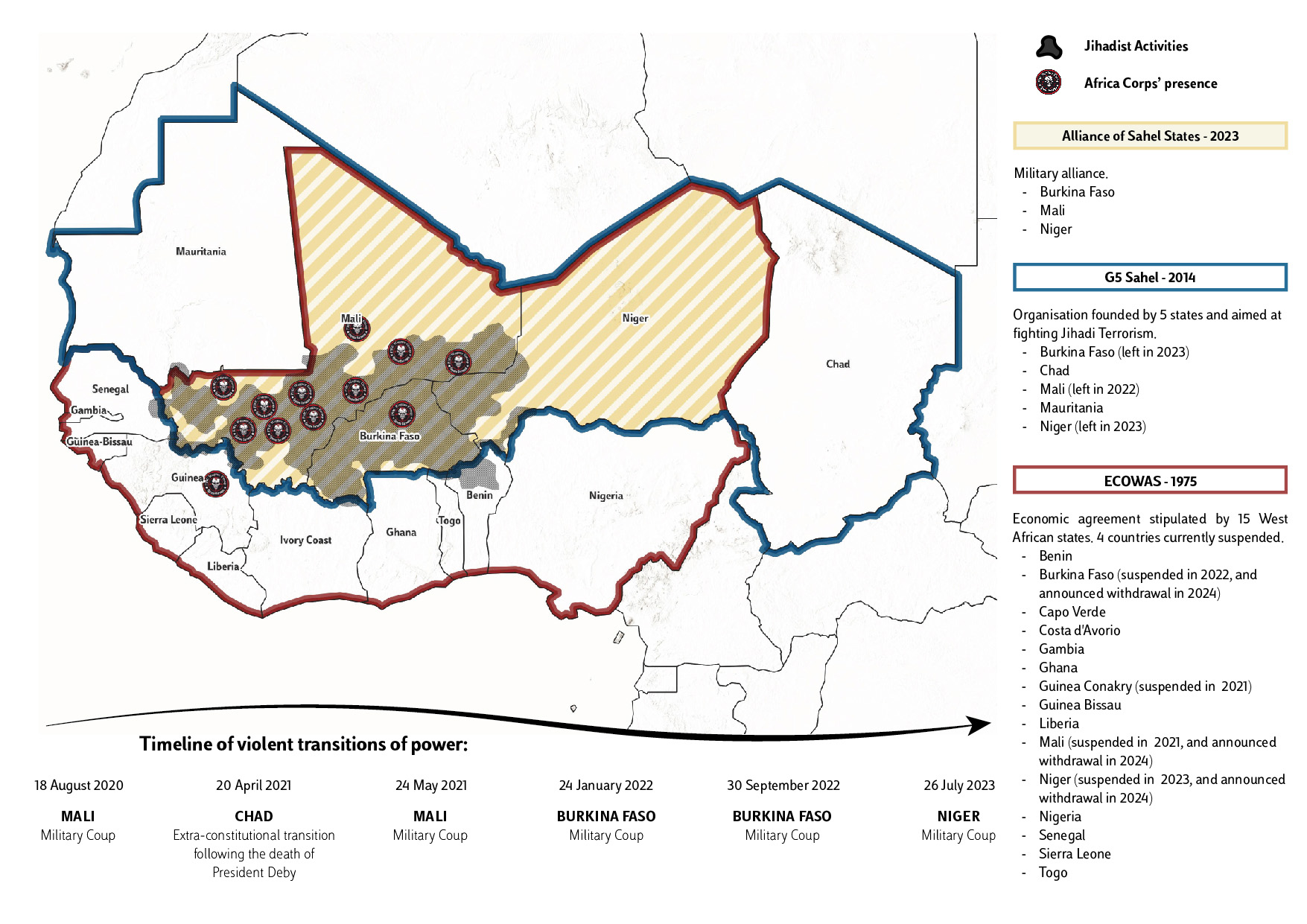

Since 2020, the Sahel region[2] has found itself in a new phase of acute crisis. The coups in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali and most recently in Niger – once considered the West’s bulwark in the Sahel – have marked a drastic turn towards militarism and authoritarianism, increasing the burden on civilians and amplifying violence and the displacement crisisThis authoritarian spiral has resulted in a notable geopolitical shift, with the juntas aligning themselves with Russia and opening the door to the Wagner Group[4] -now rebranded as Africa Corps.[5] Regional powers have, at the same time, distanced themselves from traditional Western and regional partners. This resulted in the dismantling of the international security architecture including Operation Barkhane, Takuba Task Force, MINUSMA.[6] It also saw Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger withdraw from the G5 Sahel and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and create the new Alliance of Sahel States (ASS).[7]

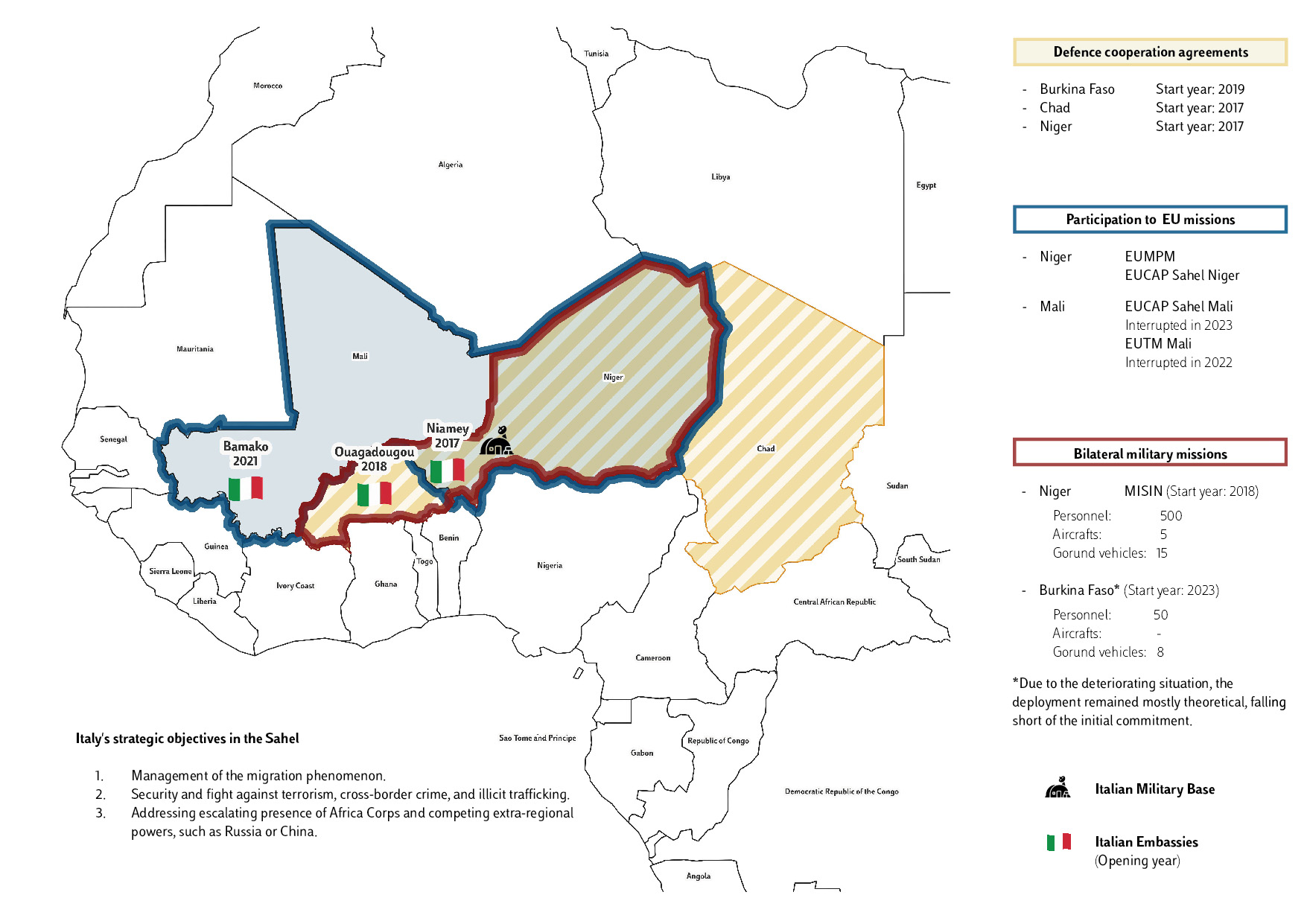

The mounting crisis has left Italy, as well as many other Western countries, disoriented, while grappling with the challenge of balancing strategic interests with their commitment to democratic values. Within this context, the risk that the West is marginalised in the Sahel is growing, jeopardizing the hard-won gains achieved in the last decade. It is only in the last years that Italy has begun to recognize the strategic significance of this region, as part of a broader shift towards sub-Saharan Africa[8], intensifying its diplomatic, military, and political involvement (see Box). The heightened attention to the Sahel has been primarily driven by two strategic objectives: managing migratory flows; and combating terrorism, cross-border crime, and illicit trafficking.[9] The ongoing Sahelian crisis, coupled with the dramatic war unfolding in Sudan, is likely to further exacerbate migration concerns, turning a dire situation from bad to worse. Recently, a third objective has emerged: the need to address the growing presence of former Wagner and extra-regional powers, such as Russia or China.[10]

This Policy Paper aims, in a period of uncertainty and volatility, to offer strategic insights into Italy’s engagement options in the Sahel. Rome cannot afford to relinquish its aspirations for a leading role in the area, particularly in light of the recently approved Mattei Plan for Africa. To recalibrate Italy’s presence in the region, this Paper outlines potential developments in the Sahel presenting alternative scenarios. Using this analysis as a guide, it then explores Italy’s options and their likely potential impact and identifies avenues to action. Specifically, in charting Italy’s path forward, the Paper addresses three sequential strategic questions:

- Should Italy maintain its engagement in the Sahel?

- If yes, what results could Italy realistically pursue in the current limited context?

- How can Italy steer its engagement to achieve these results?

1. Sahelian scenarios

A first question is: where is the region heading? To navigate uncertainty and effectively gauge Italy’s likely influence on the future of the region, a scenario analysis is a valuable endeavour. This analysis presents four distinct scenarios that could unfold based on decisions made today, projecting potential developments in three critical domains: Sahelian internal politics; geopolitical context; and security[11]. The four scenarios are: the worst-case scenario, with the most challenging and dire circumstances; the first-best scenario, the ideal outcome, with the achievement of Italy’s three strategic objectives; the second-best scenario, offering a less positive pragmatic but achievable result; and the illusory first-best scenario, appearing perhaps ideal but likely to deteriorate into the worst-case scenario due to a focus solely on superficial and short-term outcomes.

Figure 1: Sahel in turmoil

Source: 2023 Annual Report on Security Information Policy

Point of no return (worst-case scenario)

- Power rests in the hands of the elite and military groups, primarily focused on consolidating their authority, with little concern for the well-being of local populations; in many cases, juntas have been overthrown by opposing military factions, making ‘coup within coup’ a common occurrence.

- The Sahel is in the sphere of Russia and other hostile actors, while Western nations, including Italy have now been completely ousted from the region; regional cooperation is irreparably compromised, while other African countries have deployed troops under bilateral agreement to protect the government in exchange for the control of mining.

- Jihadist groups have consolidated their power and extended their reach into the Gulf of Guinea, utilizing the Sahel as an operational hub. Violence by self-defence militias has escalated, pushing more civilians to join armed groups for protection. The intensification of conflicts and the deterioration of socio-economic conditions have led to a dramatic increase in the number of migrants fleeing northward.

Better than all the rest (first-best scenario)

- The military has overseen the restoration of a substantially democratic transition; new inclusive social pacts have been signed between central authorities and opposition actors and non-state armed groups, excluding though extremist groups.

- Sahelian countries uphold robust and cross-sectoral relations with Italy, as well as with the European Union (EU) and regional organizations; the influence of Russia has been effectively contained.

- Internal security has returned to state control, with the disbandment of self-defence militia; the local-led peacebuilding process has enabled a significant reduction in intercommunal violence and the terrorist threat has been effectively contained.

Oasis in turmoil (second-best scenario)

- While the political landscape remains precarious, national reconciliation processes have been initiated between military authorities and non-state actors, other than extremist groups; local agreements between communities have, in some cases, been signed to address grievances.

- Despite the continued presence of Russia, both populations and governments have begun to recognize the risks associated with this actor; efforts have been made to re-establish dialogues with Italy and European partners, as well as with the ECOWAS and the African Union.

- Terrorist groups persist in exploiting states’ vulnerabilities, but efforts have been made to reduce jihadist expansion, as well as to address the underlying drivers of radicalization; central authorities have partially managed to bring self-defence groups under some sort of state control, contributing to a reduction in inter-ethnic and inter-communal violence.

Mirage of stability (Illusory first-best scenario)

- To appease Western demands for a return to democracy, the juntas have either conducted symbolic elections or installed a civilian-led transitional government devoid of real power; what may appear as democratic progress is a strategic manoeuvre by the juntas to gain token legitimacy, thereby reinforcing their grip on power.

- Initially rejecting ex-Wagner operatives’ assistance in exchange for the resumption of Western humanitarian aid and financial support, the juntas eventually accepted Africa Corps’ involvement to maintain power; in other cases, ‘coup within coup’ scenarios occurred, with officials overthrowing juntas that had aligned with the West, tilting their nations again towards the Russians.

- Despite their initial reservations regarding democracy and civilian protection, Western powers resumed security assistance to further their interests amidst intense great-power competition. However, this strategy was short-lived, as juntas found more favourable arrangements with the Russians, leading to a shift in alliances.

2. To engage, or not to engage, this is the question

Having seen the possible scenarios, let’s now look at the engagement options. Faced with democratic regression in the Sahel, should one persist with engagement or opt for disengagement, which would entail severing ties with military regimes and imposing sanctions? This dilemma encapsulates the enduring tension between upholding values and pursuing interests.[12] The malaise is evident when looking at the EU’s see-sawing reaction to the coups in the Sahel, which ranged from a hard-line stance, in the case of Niger, to a soft approach, with Chad, or a more ambiguous response, in Burkina Faso and Mali.[13]

When opting for full disengagement, the effectiveness of a hard-line stance must be evaluated in relation to the desired objective, namely the return to constitutional order and improvement in stability. Upon analysing the outcomes thus far, this assessment yields negative results.[14] Diplomatic isolation and sanctions have proven to be ineffective both as an ex-post response (military coup regimes remain firmly entrenched in power) and as an ex-ante deterrent measure (coups have increased in recent years). In essence, disengagement merely perpetuates the status quo, or, worse , pushes the region towards the ‘point of no return’.

Disengagement has proven to be not only ineffective but even counterproductive. On the socio-economic front, sanctions have exacerbated poverty and food insecurity among vulnerable groups.[15] On the political front, sanctions and diplomatic isolation wield a double-edged sword. Domestically, they have served as a tool to rally the population against Western powers, triggering a wave of national pride that has benefited the military regimes. Externally, they have increased resistance to Western countries, pushing Sahelian governments towards Russia. The limited impact of sanctions on coup leaders is confirmed by the U-turn adopted by ECOWAS, which opted to lift the sanctions once Bamako, Ouagadougou, and Niamey declared their intention to withdraw from the organization.[16]

In summary, it would be naive to believe that disengagement from the Sahel alone could reverse coups, restore democracy, and reduce instability.[17] This viewpoint was clearly articulated by Italian Foreign Minister Tajani, who stated that ‘the withdrawal from the Sahel, supported by some of our European partners, would make the region more hostile and certainly not more conducive to our strategic interests’.[18] Italy has taken steps to show its willingness not to withdraw, yet its initiatives remain fragmented and struggle to align cohesively, as it confronts with the challenge of balancing values and interests. While Italy ceased its contributions to EUCAP and EUTM Mali in 2023, it simultaneously launched a new bilateral military mission in Burkina Faso that same year.[19] Regarding Niger, Italy attempted a delicate balance, endorsing the EU’s sanction regime while working to keep bilateral relations open. As part of this effort, the bilateral military mission in Niger (MISIN) was extended until December 2024 and in March 2024 a joint mission was conducted in Niamey by the Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Head of the Joint Operations Command (COVI) to investigate avenues for revitalizing bilateral cooperation.

While seeking to clarify its role in the Sahel, Italy has recently signed new migration deals with Northern African countries[20], a move that could be interpreted as an attempt to build a sort of ‘safety net’ to contain migration flows from the Sahel. However, this strategy merely echoes the border externalization policies of the past, which have already proven ineffective in managing migratory flows.[21] The ongoing Sahelian crisis, coupled with the Sudanese war, is likely to exacerbate the migration situation, making this “safety net” even more inadequate in the face of unfolding events. Burkina Faso and Mali were among the top nationalities arriving in Italy by sea in the first half of 2023.[22] This is another crucial reason for Italy to engage in the Sahel, working to address the root causes of migration and to create the conditions for a less conflict-ridden landscape.

3. Defining ambitions: What should Italy seek in the Sahelian sands?

Having clarified the realistic options, we can now look at the strategic implications. While committing to engagement is an essential first step, it is, in fact, not sufficient for significant positive results. Indeed, the option of ‘engaging’ has been pursued so far by the EU and member states, but their approach, anchored in security concerns, has ultimately led to unstable outcomes and contributed to the deteriorating situation we observe today. Note here the shortcomings of Operation Barkhane and Takuba Task Force, and the erroneous belief that stabilization could lead to development and state restoration, thereby fostering stability and reducing migration flows.[23] Similarly, considering the Sahel as a geopolitical chessboard with the sole aim of excluding competing actors has also resulted in ephemeral outcomes. Niger is a case in point: after the coup, Washington indicated its intention of maintaining troops in the country with an anti-Russia intent.[24] But this arrangement proved short-lived, as the ruling junta revoked the military accord with the US within less than a year, tilting towards the Russians.

Figure 2: Italy in the Sahel

Source: DOC. XXVI – N. 2 “Extension of International Missions and Cooperation Interventions for the Year 2024. Review of the Resolution of the Council of Ministers February 26, 2024.

These lessons should be integrated into Italy’s approach to the region so Europeans avoid being mesmerized by the ‘mirage of stability’. When engaging in security-driven, realpolitik cooperation with juntas, Italy should be mindful of how quickly such arrangements can break down, leaving it empty-handed and exposing its flank to anti-Western propaganda. Acknowledging this reality means accepting that, given the current limited context, the first-best is not achievable in the short term. Strategically, this requires lowering ambitions and aiming for realistic intermediate results. At present, these might include: i) maintaining an Italian presence in the Sahel; and ii) mitigating the pressure on civilians while laying the groundwork for a less fragmented and conflictual political landscape.

With this realistic approach, Italy can contribute in the short term to paving the way for the Sahel to move towards the second-best scenario, thereby preventing the region from reaching the point of no return. By maintaining a presence there, Italy could influence some key political processes and credibly advocate for inclusive political outcomes. Simultaneously, protecting civilians as violent conflict and casualties spiral out of control would help prevent marginalized and vulnerable groups from turning to armed groups or from being forced down dangerous emigration routes.

Securing these intermediate results would pay off in the long run by creating conditions that structurally safeguard Italy’s strategic objectives. Rather than pursuing short-term and superficial outcomes, this longer-term strategic approach would enable Italy to credibly support Sahelian authorities on the path toward democratic and inclusive solutions, particularly following power-sharing agreements with opposition and non-state armed groups, other than extremist groups. Addressing the socio-economic drivers of conflict and fostering long-lasting economic opportunities are crucial for mitigating migration and violent extremism drivers. Moreover, a presence in the Sahel would serve as a bulwark against competing geopolitical interests, including those of Russia.

4. Remaining in the Sahel: How?

After strategy, comes implementation, which raises the “how” question. While coup leaders have fostered an anti-Western narrative, they have not entirely closed off the lines of communication, leaving room for potential engagement. In particular, Italy still retains a degree of manoeuvrability and strategic advantages, including its diplomatic and soft power assets which can be leveraged to attain intermediate goals. Moreover, Italy is not burdened by significant colonial legacies here and is perceived as less deeply enmeshed in global power dynamics. Rome should thus capitalize on these advantages and shape its engagement around two pillars: dialogue and diplomacy. In this regard, some strategic-level considerations can be elaborated.

- Italy could usefully identify venues for bilateral government-to-government discussions. Such actions, which would confer a degree of legitimacy upon military juntas, could then be leveraged to encourage coup leaders to engage with opposition parties and non-terrorist armed groups, to negotiate power-sharing agreements and establish transition roadmap. The aim would be to mitigate insecurity and volatility. In particular, Italy might advocate for the resumption of negotiations under the Algiers Peace Agreement, which, despite being denounced by the Malian authorities, remains the most viable option at the moment. In addition, Italy could explore venues for national authorities to develop and implement programs for the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of former combatants, as well as strategies for dismantling militias and self-defence groups, or at least establishing greater control and accountability over them.

- In adopting this dialogue-driven approach, Italy should carefully consider appropriate sequencing. Initially, dialogue should prioritize reaching agreements with governments on the delivery of basic services and humanitarian aid, alongside the promotion of certain stopgap income-generating projects. By prioritising less sensitive issues like improving livelihoods, Italy can simultaneously ease the burden on civilians and establish credibility and confidence, thereby avoiding perceptions of bias or excessive intervention. As trust strengthens, more sensitive topics can be introduced into the dialogue, focusing government-to-government discussions on priorities aligned with Italy’s foreign policy agenda, minimising the risk of resistance or backlash from diverse stakeholders.

- Alongside top-down mediation efforts, Italy could also promote a parallel bottom-up approach. Indeed, central authorities, whether military or civilian, maintain control over only a portion of the national territory, while communities serve as the foundational units of governance systems.[25] This means that even if a national agreement is reached, lasting peace cannot be guaranteed if local communities are not involved. To accomplish this, Rome could signal its belief in and support to Italian non-institutional players, who can assist mediation initiatives on the ground, particularly those led by local organizations rooted in local ownership.

- Italy could bolster its engagement in the Sahel by aligning diplomatic efforts at the European level to mitigate rivalry risks and to capitalize on synergies within the EU. With French influence having diminished in the Sahel, Italy finds itself in a good position for revamping EU-coordinated efforts in the region, while exploiting the potential for close collaboration with Paris. A window of opportunity seems to be confirmed by the recent affirmation the Foreign Affairs Council[26] for the EU to remain committed to the Sahel, followed by the decision to adopt ‘a more transactional approach’.[27] Rome can play a key role in defining this ‘transactional approach’ in practical terms, steering Europeans towards a dialogue with the juntas.

- Italy should prioritize Sahel in its strategic and financial planning, translating the framework provided in this Brief into actionable plans tailored to the specific context of each country. With this vision charting the path forward, the Italian authorities would be able to determine, on a case-by-case basis, where, when, and with whom to employ the diplomatic and soft power assets at their disposal, all while maintaining a sense of the overall direction. To coordinate actions and ensure internal consistency, the appointment of a special envoy for the Sahel might prove beneficial. Moreover, scaling up the exercise of designing the ‘Sahelian scenarios’ outlined in this Brief would be crucial in mitigating the risk of unexpected events and enhancing situational awareness.

- Emphasis should put on enhancing public diplomacy to better communicate Italy’s message and counteract Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI). This is a critical step considering the rise of anti-Western propaganda and the increasing corruption of the information space, particularly orchestrated by Russia. Strengthening public diplomacy efforts will not only enable Italy to maintain a presence and prevent backlash from populations and institutions but also foster trust and credibility, thereby safeguarding Italy’s presence in an increasingly complex global landscape.

Concluding remarks

The significant progress Italy has achieved over the past years in the Sahel is now at risk amidst the wave of coups. To step back from the ‘point of no return’, Italy needs a strategic recalibration, recognizing that military juntas, while not ideal partners, will likely remain key players for the foreseeable future. Italy has acknowledged the importance of continued engagement in the Sahel. However, a comprehensive strategy has yet to emerge, caught as Italy is between balancing interests and values and navigating divergent policies within the EU. This strategy is more crucial than ever, as the burden on civilians has become overwhelming, and the risk of Italy being permanently ousted from the region is increasing and the growing displacement crisis cannot be managed simply through border externalisation policies. Italy should draw from past lessons, while acknowledging another hard reality: engagement requires time and results take time. Setting realistic ambitions, pursuing dialogue and leveraging diplomatic and soft power assets should steer Italy’s Sahel strategy.

References

[1] The author is grateful to Luigi Narbone, Virginie Collombier, Giovanni Faleg and Luca Raineri for their invaluable inputs in preparing this Brief. He would also like to thank Ayoub Lahouioui for designing the infographics and Meraf Villani for her research assistance.

[2] Geographically, the Sahel reaches from the Atlantic coasts of Mauritania and Senegal to the Red Sea coast of Sudan and Eritrea. This Brief focusses on the core Sahel countries central to recent developments: Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Niger

[3] ACLED, “Fact Sheet: Attacks on Civilians Spike in Mali as Security Deteriorates Across the Sahel”, September 2023.

[4] While ex-Wagner operatives are well consolidated in Mali, signs of their presence have also being noted in Burkina Faso and Niger. In January 2024, Africa Corps troops reportedly landed in Ouagadougou, marking the initial phase of a three-hundred-member force deployment. The Nigerien junta signed a protocol agreement with Russia in December 2023 and in April 2024, approximately 100 Russian military instructors and with associated material arrived in Niamey and Africa Corps announced its presence in Niger via social media. Source: CrisisWatch of the International Crisis Group)

[5] Following the demise of the group’s founder Yevgeny Prigozhin, the group has reportedly come under the direct control of the Russia’s Ministry of Defense and has been renamed Africa Corps.

[6] After successive military coups in August 2020 and May 2021, the Malian junta escalated their efforts to oust France and other European forces from the country, culminating with the expulsion of the French Ambassador. Consequently, in February 2022, President Macron announced the complete withdrawal of both Barkhane and Takuba forces from Mali. Similarly, in February 2023, upon the request of the Malian authorities, the UN Security Council decided to terminate the mandate of MINUSMA.

[7] The ASS was conceived as an alliance for mutual self-defense and assistance, with articles 5 and 6 enabling collective defense against aggression and insurgencies, including terrorism. In March 2024, the ASS announced the creation of joint counterterrorism force to combat regional jihadist insurgency and to address shared security needs.

[8] Faleg G. and Palleschi C., “African strategies. European and global approaches towards sub-Saharan Africa”, EUISS Europe Chaillot Papers, 30 June 2020; Carbone G., “Italy’s return to Africa: between external and domestic drivers”, Italian Political Science Review, 53(3):293-311, 2023.

[9] Sistema di Informazione per la Sicurezza della Repubblica, “Relazione annuale sulla politica dell’informazione per la sicurezza”, 2023.

[10] China’s presence in the Sahel has been so far considerably less extensive and less military-focused than Russia’s, being primarily driven by economic and political concerns. With the West withdrawing from the Sahel, the conclusion of MINUSMA, and the de facto dissolution of the G5 Sahel, Beijing might consider reviewing its commitment to the region and stepping up its role also as a military actor. Notably, in April 2024, officials of the Nigerien junta discussed strengthening defense cooperation with the Chinese ambassador (source: CrisisWatch of the International Crisis Group).

[11] This scenario-building exercise contemplates a range of alternative possibilities that could unfold based on decisions made today. Following a comprehensive assessment of the current situation, three primary categories of actors were identified: state actors, non-state actors, and extra-regional powers. For each category, a set of potential choices was meticulously crafted. By combining these sets of choices actor by actor, potential developments were then projected in three critical domains: domestic politics, geopolitical context, and security. Finally, depending on their nature, these developments were categorized into four distinct scenarios: worst-case, first-best, second-best and illusory first-best scenarios.

[12] Wilén N., ‘Have African coups provoked an identity crisis for the EU?’, Egmont Policy Brief No 323, December 2023.

[13] After the initial coup in Mali, the EU temporarily halted civilian CSDP missions, later resuming them following an agreement with ECOWAS on a transition timeline. Following the second coup, the EU condemned the change of government only one week after, and then approved a framework for additional sanctions and the suspension of operational training activities. In Burkina Faso, the EU High Representative condemned the coup but stated that more time was needed to assess the partnership with the EU. Regarding the coup in Chad, there was no official condemnation from the High Representative initially; it was only six months later, after the transitional military council violently repressed protests, that a statement condemning the violence was issued. In Niger, the EU swiftly condemned the coup, endorsed ECOWAS measures, and established an autonomous framework for restrictive measures.

[14] Marangio R. “Sahel Reset: Time to reshape the EU’s engagement”, European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS), Policy Brief, February 2024.

[15] The World Food Programme (WFP) has estimated that in Niger 7.3 million people may be driven from moderate to severe food insecurity as a result of the latest post-coup restrictions. Source: World Food Programme and the World Bank, “Socio-economic impacts of the Political Crisis, ECOWAS and WAEMU Sanctions and Disruptions in External Financing in Niger”, October 2023.

[16] Le Cam M. “From Niger to Guinea, ECOWAS sanctions against juntas have failed”, Le Monde, 28 February 2024.

[17] Ero C. and Mutiga M., ‘The crisis of African democracy: Coups are a symptom – not the cause – of political dysfunction’, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 103, No 1, 2024.

[18] Communications to Parliament’s Foreign and Defense Committees by Ministers Tajani and Crosetto, 19 March 2024.

[19] Due to the deteriorating situation, the deployment has remained mostly theoretical, falling short of the initial commitment.

[20] Mezran K and Pavia A. “Giorgia Meloni’s Foreign Policy and the Mattei Plan for Africa: Balancing Development and Migration Concerns”, Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), July 2023.

[21] Martini L. S. and Megerisi T., “Road to Nowhere: Why Europe’s Border Externalisation Is a Dead End”, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), December 2023.

[22] Sahel situation, UNHCR, accessed 1 June 2024, https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/sahel-situation.

[23] Raineri L. e Rossi. A, “The Security–Migration–Development Nexus in the Sahel: A Reality Check” in “The Security–Migration– Development nexus revised: a Perspective from The Sahel” (edited by Venturi B.), Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), 2017.

[24] As of December 2023, approximately 648 United States military personnel remained deployed to Niger. Source: White House, “Letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and President pro tempore of the Senate regarding the War Powers Report”, 7 December 2023.

[25] Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, Mediation of Local Conflicts in the Sahel Burkina Faso, Mali & Niger, 2022.

[26] Foreign Affairs Council, 11 December 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/fac/2023/12/11/.

[27] Foreign Affairs Council, 19 February 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/fac/2024/02/19/.

In focus

Levels of Government and Administrative Boundaries in Libya’s Future Local Governance System

KHERIGI, Intissar

2 July 2025

The GCC States’ Security Policies in the Red Sea Geopolitical Border: Factors and Policy Options

ARDEMAGNI, Eleonora

26 June 2025

Sleepwalkers into War Are Algeria and Morocco on the Path to Conflict?

KHECHIB, Djallel

25 June 2025