Prospects of Local Governance in Libya: Framing the Debate for Post-Conflict Stability

Introduction

The 2011 uprising in Libya raised the question of the equitable distribution of power and wealth among all regions of the country and demands for participation in decision-making at the local level. This paper examines the issue of local governance in Libya from its recent history to the present, considering cultural, political, social, and institutional factors. It analyses how the local governance system could be developed to meet the aspirations and demands of the Libyan people.

Agreeing on a new model of local governance in Libya is no easy task, given the existing political and social divisions that have been deepened by the civil war. But why should there be discussion of local governance and decentralisation considering the existing fragmentation of the state?

First of all, because it is a theme consistently raised by Libyans themselves. Local governance and decentralisation have been raised in public debate since February 2011, although these terms mean different things to different people. As discussed in the paper, these terms are often raised to give expression to demands such as political and economic inclusion, public participation in decision-making and a just distribution of resources.

Secondly, the Libya roadmap for the “Preparatory Phase for a Comprehensive Solution” that emerged out of the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum mentions strengthening local governance as one of the key themes that need to be addressed in order to solve the crisis. Many actors propose local governance reform as a conflict-resolution mechanism that could help resolve Libya’s highly complex conflict and address its root causes. Simply put, the idea is that dividing up power and sharing resources between different regions and levels of government could help reduce a “winner takes all” approach to gaining power at the top. Competition over institutions that centralise power and resources in a few hands, the argument goes, would be dispersed, and de-escalated. Some also suggest that including expanded local autonomy as an element of Libya’s peace settlement would act as a confidence-building mechanism, signalling that the future governance system will not allow any one side or region to exert a monopoly on power.

The idea that rethinking local governance can help resolve Libya’s conflict has been raised repeatedly by participants in the Peace Makers Libya dialogues with social and political leaders and intellectuals in the country. As expressed by many of the participants in these dialogues, as well as those we spoke to while preparing this paper, decentralisation of powers and resources is key to building a lasting peace that is just, inclusive and sustainable. Simply reconstituting Libya’s highly centralised state, along the pre-2011 governance model, would do nothing to address the grievances and demands of Libyans.

Thirdly, the war in Libya has led to de facto decentralisation in various localities. The political and military conflict has produced a deep polarisation and a multiplicity of centres of power, each with their own peripheries. Some localities have developed their own forms of local governance, and municipalities have gained new powers and resources under the law. Tribes are also exercising a significant role as the reach of the central state has shrunk. Local governance is, in reality, exercised by a web of local tribal and military councils alongside – and sometimes within – municipalities. It is difficult to envisage a return to highly centralised rule in light of these changes.

But what local governance are we talking about? It is clear that there are a variety of different, and often conflicting, visions of which model of local governance would be best for Libya’s context.

This paper is based on interviews with various stakeholders in Libya, including experts in local government, academics, and representatives of political and social groups, as well as an in-person workshop with Libyan representatives held in Rome in February 2024. In addition, it draws on a desk review of existing studies and primary materials on the history of local governance in Libya and its challenges today.

These reveal various visions in Libyan political and civil society regarding what kind of local governance system could meet the needs and aspirations of the Libyan people and support social, political, and territorial cohesion. In this paper, we map these into three overall groups – pro-federalist, pro-decentralisation and pro-centralisation. Each of these groups contains within it a range of views on the optimal system of local governance that could achieve balance between Libya’s regions, take account of national and local specificities and give local authorities and communities the ability to participate in the management of local and national affairs while maintaining and strengthening the unity of the Libyan national state.

It is important to note here that decentralisation in a post-conflict context involves particular complexities. The issues of decentralisation and local governance are extremely politicised in the current context, and even the terms themselves are highly contested. While some Libyan actors use the term “decentralisation” to refer to the transfer of powers and resources to a subnational level, others utterly reject it on the basis that it refers to an illegitimate, watered-down form of local governance. There is little consensus on the terms to use, let alone their substantive content. In addition, the same term is often used in different ways. These differences often lead to an impasse in any discussion on local governance.

This paper focuses on the different definitions, meanings, and dimensions of decentralisation and local governance. It begins by clarifying and defining the different terms relating to local governance, before moving to examine the history of local governance in the Libyan context and the preferences of Libyan political and social actors with regards to a future system of local governance.

The paper is the first in a series of papers on the future of local governance in Libya, each of which focuses on a different dimension of local governance – levels of government, distribution of powers, and distribution of resources. By clarifying concepts, mapping positions, and mobilising experiences from other contexts, we seek to spur reflection and create space for discussion between Libyans and enable them to examine and evaluate the different options available to them and their potential risks and outcomes, with the aim of reaching a local governance system that meets the needs and aspirations of the Libyan people.

1. Terminology

1.1. Defining decentralisation

At the outset, we define decentralisation as a system or process for distributing or assigning powers to subnational authorities that: are autonomous or semi-autonomous, meaning:

- They have legal personality.

- They enjoy a significant degree of financial and administrative autonomy (enjoy their own financial resources).

- Enjoy political decision-making power to issue their own decisions and use their resources without needing prior approval of central authorities.

- Not subject to the direct control of central government (subject only to a posteriori, not a priori, oversight).

- Representative of the residents of the area (not of the central state).

The term decentralisation is used to describe different systems that can be either unitary or federal. Most countries in the world have engaged in some form of decentralisation in the management of public governance. Decentralisation is based on the idea of proximity and the assumption that bringing decisions closer to the local level is expected to lead to better service delivery, faster interventions, better resource mobilization, increased accountability, and higher citizen participation, among other things.

In Libya, the term “local administration” (al-idara al-mahaliyya) is used to describe the current local governance system. It should be noted that this differs from decentralisation in two key ways: in the “local administration system”, local authorities[1] perform their tasks under the supervision of the central authority and enjoy very limited powers and resources. These two elements (central oversight and distribution of powers and resources) are what make decentralisation different from deconcentration, as explained further in the next section.

1.2. The difference between decentralisation and deconcentration

It is necessary, from the outset, to distinguish between decentralisation and deconcentration, given that there is often confusion when discussing the two.

Decentralisation is based on granting local authorities administrative and financial independence, which is set out in the constitution and relevant laws. The decentralised system – whether in a unitary or federal system – is based on the distribution of decision-making powers, not just implementation powers, and this is what distinguishes decentralisation from decentralisation. Decentralisation grants local authorities greater powers to decide for themselves their own policies on how to spend resources and how to provide services.

Meanwhile, deconcentration can be defined as a method of administrative organisation that delegates or assigns tasks to branches or territorial structures affiliated with the central authority. These territorial structures can be considered as agents of the central state (delegate/agent) because the decision-making power belongs to the centre. The central authority can terminate the delegation and return authority to the central level at any time. For example, any ministry can establish local structures affiliated with it to provide services to citizens at the local level (such as local offices of the Ministry of Education or Agriculture, etc.). The local structures are responsible for implementing the policies and decisions set by the central ministry, their employees are appointed by the central ministry and the resources come from the central ministry. The ministry can limit or revoke the powers of its local structures or even dissolve them.

Thus, there is a big difference between deconcentration and decentralisation, mainly relating to the transfer of political decision-making power, and financial, legal, and administrative autonomy.

1.3. Federalism

Federalism can be considered to be one of the strongest forms of decentralisation and is one of the most important forms of government throughout the world. In a federal system, the constitution establishes federal and subnational authorities, and sets out the distribution of powers between them. Among the most prominent countries in the world that have a federal system are Austria, Argentina, Australia, the United States of America, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the United Arab Emirates, Canada, Brazil, Germany, India, the Comoros, Ethiopia, Malaysia, and many other countries.

One of the most important features that distinguish the federal state is that powers are constitutionally divided between a federal or central government and regional and/or local governments that enjoy a great deal of autonomy. This means the distribution of powers cannot be changed easily, usually requiring a constitutional amendment. In most federal systems, local authorities also enjoy legislative and judicial powers, defined in the constitution. For this reason, the federal state is known for its multiplicity of legal systems, while the unitary state is characterised by the unity of law throughout its territory.

It is important to note that there are centralised federal states just as there are decentralised federal states. Similarly, unitary states can be centralised or decentralised. This highlights the importance of avoiding an excessive focus on the names or labels used to describe a system. As mentioned above, it is more important to think through how the local governance system will work, i.e. the distribution of powers and resources between the different levels of government and how they would work together.

1.4. Dimensions of decentralisation

Decentralisation has three main dimensions, which are:

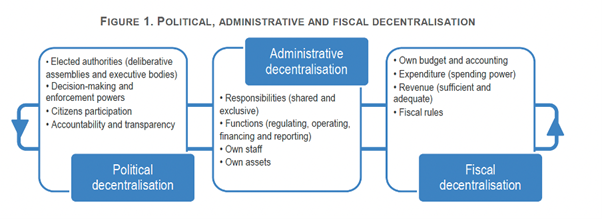

- Administrative or functional decentralisation: the distribution of powers/functions between the central authority on the one hand and independent subnational units on the other hand.

- Political decentralisation: local officials are selected at the local level (rather than being appointed by the centre), usually through elections that allow citizens/residents to choose their representatives, express their priorities, and hold local officials accountable.

- Fiscal decentralisation: these include giving local authorities (1) decision-making powers to dispose of resources; (2) powers to collect revenues; (3) powers to impose new taxes or duties; and (4) a greater proportion of the resources extracted at the national level.

Figure 1: Definitions of political, administrative, and fiscal decentralisation

Source: OECD, Making Decentralisation Work: A Handbook for Policy-Makers, 2019

1.5. Local autonomy: a posteriori vs. a priori oversight

In any decentralisation process where local authorities are to enjoy legal and administrative autonomy, it is essential to remove most forms of a priori oversight. It is useful to distinguish here between a priori and a posteriori oversight powers. A priori oversight makes local authorities’ decisions, minutes, and budgets subject to the prior approval of central authorities in order to be valid. For example, if a municipality or province cannot officially adopt its annual budget without the prior approval of the central government or a centrally appointed regional governor. A posteriori oversight means legal oversight and financial monitoring of local authorities’ decisions after they have been issued. This can be by the central government or a financial monitoring agency or the judiciary.

In the highly centralised systems in place in much of the Arab world, local authorities – even when elected – are subject to extensive a priori oversight by national authorities. For example, the law may provide that the decisions and budgets of local authorities will not be valid without the authorisation of national authorities. The law usually also allows appointed regional governors to intervene significantly in the work of regions/provinces and municipalities. This gives a great degree of control to central authorities, especially the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Finance.

In Tunisia, for example, the wali (regional governor) appointed by the central government historically enjoyed a double role both as the administrative representative of the central state at the governorate (wilaya) level and as the head of the (nominally elected) regional council, a political decision-making body. To end this centralised control, Article 138 of the 2014 Constitution explicitly states that “local authorities are subject to post-facto oversight to determine the legality of their actions” (our emphasis). This makes clear that local authorities’ decisions and actions cannot be subject to prior approval and that they can be subject to oversight relating only to their respect for the law (contrôle de légalité) but not relating to the substance of their actions or decisions (contrôle d’opportunité).

The principle of local autonomy for regions/provinces and municipalities also applies to the relationship between these two subnational levels. During discussions with Libyan actors, some expressed the idea that decentralisation should start by defining the powers of regions/provinces and holding elections for these before defining the powers of municipalities. Some even suggested that regions/provinces should be responsible for defining the powers of municipalities and even overseeing them. It should be noted that giving regions or provinces oversight powers over municipalities creates serious risks for municipal autonomy.

2. The context of local governance in Libya

2.1. Historical context

The local governance system in Libya has been shaped over centuries by particular social, geographical, political, and cultural specificities, namely:

- The diversity of tribes and clans, each of which inhabits a geographical area, and each characterised by cultural, social, and historical peculiarities and differences in customs and traditions that are important to its members.

- Geographical factors: Libya’s large size and the diversity of its ecosystems between the African desert and the Mediterranean coast, with a large percentage of the population concentrated in a small percentage of its territory.

- The political system: all those who ruled Libya in the past centuries sought to exert territorial control by using a combination of alliance-building and repressive strategies towards tribes and clans, which contributed to amplifying the competition between them and increasing their authority at times. This also had an impact on the territorial division of Libya, where provinces, regions, municipalities, and other territorial divisions were created based on the historical borders of the tribal areas.

2.2. Evolution of the local governance system

Local governance is not new to Libya and dates back several centuries. Under nominal Ottoman rule since 1551, Libya underwent significant administrative reorganisation in the second half of the nineteenth century after the re-establishment of direct Ottoman rule in 1835. The 1864 law of provincial administration reorganised the territory into provinces (wilaya) and, below them, local districts (sanjaq). In 1871, the revised provincial administration law established the municipality as an administrative unit, each with a mayor and advisory municipal council.

Following Italian colonisation in 1911, Libya’s provinces underwent reorganisation again. A system of local assemblies with limited powers was introduced but quickly revoked. After the end of colonial rule in 1951, a federal monarchy was established led by King Idris, consisting of three autonomous provinces, namely the Cyrenaica province, the Tripolitania province, and the Fezzan province. The 1951 constitution was changed on April 26, 1963, when the federal system was abolished, and the three provinces were reorganised into 10 governorates.

After Muammar Gaddafi’s rise to power in a coup in 1969, local governance witnessed many changes in accordance with the regime’s philosophy and the idea of “popular administration.” This period witnessed administrative instability in the organisation of administrative units and their division between governorates, municipalities, municipal branches, and subdistricts. Local authorities, in their various forms and types, were subject to complete loyalty to the existing central authority, which had absolute jurisdiction to divide the regions, determine their forms, control their borders, and name those in charge of them.

The involvement of the Libyan people in an uprising against the regime of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 provided the opportunity for citizens to raise demands and grievances regarding territorial marginalisation, lack of basic services in various regions, and the distribution of resources. The uprising led to attempts to build central and local institutions based on free and direct elections. This was embodied in the election of the National Council, and in July 2012, the National Transitional Council issued Law No. 59 of 2012 on the Local Administration System, with executive regulations issued in April 2013. Pursuant to the law, 99 municipalities were established, and municipal elections were held in 2014 for the first time in the history of Libya. However, municipalities struggled to establish their authority in the face of the historical factors described above, the repercussions of the civil war, divided state institutions, and the existence of two ministries of local government, as discussed further in the next section.

2.3. Law No. 59 of 2012

Law 59 of 2012 on Local Administration represents the main legal framework for regulating local governance in Libya currently. The law stipulates two levels of local government: governorates and municipalities, which enjoy legal personality and financial management autonomy. The law stipulates that governorates and municipal councils must be elected. Several regulatory decisions have been issued based on this law and its executive regulations, most of which relate to municipalities, their tasks, administrative structure, and financial resources. Here, we note that the legislator considered governorates and municipalities to be units of “local administration” and not local authorities.

It is also questionable whether local authorities enjoy much independence in light of the oversight powers given to central government. For example, Article 4 of the law stipulates that local administration units exercise their powers “under the direct supervision of the governor,” and Article 23 stipulates that the governor, in his relationship with municipalities, “has the right to issue… instructions… that are enforceable.” The law also gives provincial councils the authority to withdraw confidence from mayors of municipalities within their territory.[2] These provisions appear to deprive municipalities of much of their decision-making autonomy. The elected provincial council is headed by a governor who is appointed and dismissed by the central authorities, which also raises questions about the independence of provincial councils.

The powers of local authorities also remain limited under the law, limited to waste collection, cleaning streets, managing parks and gardens, organising markets and public places, and road maintenance. There has been some progress in establishing the Supreme Council for the Transfer of Powers in Tripoli, composed of several ministers, which is responsible for transferring powers to municipalities. As a result, some agreements have been signed between the Ministry of Local Governance and other ministries (education, health, planning, etc.) to coordinate the process of transferring powers. However, despite much talk of transferring more powers to local authorities, progress in this area remains limited.[3]

Regarding municipal resources, the law leaves the details to a decision to be issued by the Minister of Local Administration in coordination with the Minister of Finance. Municipal revenues have been expanded by a decision by the Prime Minister of the National Unity Government in July 2021 on fees and revenues of a local nature.[4] Municipalities now enjoy the right to various revenue sources including “fees for services of a local nature, traffic violations and fines, revenues from the exploitation of public space, fees on documents issued by the municipality,” in addition to “revenues from local services, municipal guard violations and fines, and revenues from renting and investing in real estate located in the municipality.”

In addition, the Council of Ministers of the Government of National Unity issued regulations for the new Local Revenue System (MRS) in 2021, which allowed municipalities, for the first time, to collect local revenues on their own.[5] The regulations set out the mechanisms for collecting and managing fees of a local nature. The regulations stipulate that each municipality shall prepare its draft annual budget on the basis of the actual local revenues that it collects, following the methods approved by the Ministry, and submitting it to the Ministry of Local Administration. The regulations require municipalities to publish their draft budget and expenditure reports according to the citizen budget model through all available media. The government has also opened accounts for municipalities to manage their local revenues. According to available data, these decisions contributed to increasing municipal resources and enabled a number of municipalities to collect their own revenues greater than the resources transferred to them from the central government,[6] with notable progress in the performance of a number of municipalities and their ability to resolve disputes and fill the gaps resulting from the state’s inability to deliver services.[7]

The provincial level of government has not yet been established due to conflicts of a regional and tribal nature regarding their borders. Several proposals have been put forward for establishing between 10 and 18 provinces, but they were rejected by various groups.[8] Accordingly, Law No. 59 has yet to be implemented when it comes to provincial councils, and only the provisions relating to municipalities have been implemented. The absence of provinces has created difficulties in coordination between ministries and a large number of municipalities, with the absence of provinces as an intermediary structure. [9] All these challenges were and continue to be a major obstacle to the implementation of Law No. 59, as well as the existence of older laws that hinder its implementation.

Libyan stakeholders express different points of view regarding Law No. 59. Some believe that the law meets the needs of the current transitional phase and provides an appropriate framework for gradually transferring powers and resources to the local level. Supporters of the law believe that the main problem is the lack of implementation of the law and not the content of the law itself. Meanwhile, critics of Law No. 59 argue that it cannot be considered a framework for “real” local governance as it establishes “local administration” with limited powers, subject to the direct supervision and control of the central government. They argue that genuine local governance requires (1) broad powers, (2) a permanent transfer of powers (stipulated in a constitution) that the central government cannot reverse or change and (3) a reduction in the central government’s authority to intervene in local affairs.

2.4. Local governance in the draft constitution

The draft constitution that was drafted and approved by the Constituent Constitution-Drafting Assembly in 2017 contains an entire chapter on local governance. Chapter Six, Article 144 stipulates three levels of government: national, provincial, and municipal.

There are those who see Chapter Six as an appropriate framework that establishes “expansive” decentralisation and that the text does not place any restrictions on the powers of local authorities. Others believe that the terms contained in Chapter Six are unclear and allow the central authorities to control the process of selecting and transferring powers, which may lead to continued excessive centralisation. Some have expressed their rejection of the draft because it does not recognise what they consider to be the “three historical provinces.”

3. Libyan stakeholders’ views on the system of government

3.1. Which system of government?

Based on the interviews and workshop, we can identify three broad sets of views on the future local governance system among Libyan political and social actors: (a) pro-federalist views, (b) anti-federalist views with a preference for a reformed system of “expanded decentralisation,” and (c) anti-federalist views with a preference for a return to a centralised system of governance.

Supporters of “expanded decentralisation” suggest giving local authorities more powers and resources within the framework of a unitary state whose citizens are subject to a single legislative authority, constitution, government, and judiciary. Meanwhile, critics reject the term “decentralisation” altogether on the grounds that it is too vague, does not provide a basis for strong local autonomy, and gives the central state the power to interpret and control the contents of decentralisation.

On the other hand, some propose the idea of federalism, based on the diversity of Libyan society, the country’s size, and its geographical diversity. They believe that a centralised system of government has marginalised many regions and enabled tyranny and absolute individual rule. They present federalism as a solution to the power struggle between multiple centres of power by distributing power on several levels.

Federalism is defined, by its supporters, as a system that gives broad constitutional powers to governorates/provinces/regions (the terms used differ) while retaining limited sovereign functions for the central state and establishes elected executive and legislative institutions in each governorate/province/region, which enjoy all powers not explicitly reserved to the central state by the Constitution to the central state. Some have suggested that these elected provincial/regional parliaments could have powers to appoint provincial/regional governments and prime ministers and hold them to account. In addition, an elected parliament at the federal level would exercise federal legislative powers and would be composed of elected representatives in proportion to the population (and, possibly, surface area) of each governorate/province/region.

Critics of federalism, meanwhile, completely reject the idea of granting governorates/provinces/regions independent executive, legislative, and judicial institutions, citing the following arguments: a weak central state, weak human resources at the local level, the financial cost of establishing local parliaments and governments, fragile and fragmented state institutions, and the fear of the disintegration of the state or the secession of some regions.

Meanwhile, the third group (anti-federalist and pro-centralist) advocates for a return to a more centralised governance system. They emphasise the dangers of decentralisation in the current context of institutional and territorial fragmentation and argue that re-centralisation is needed before it is possible to consider expanding local autonomy. They propose that public demands for greater equality between regions can be met by expanding access to public services and infrastructure in marginalised regions and strengthening subnational government agencies.

3.2. The risks of decentralisation

Both unitary decentralisation and federalism have been used as post-conflict solutions to unify divided societies. The idea is to unite groups with different territorial bases and political, social, and economic interests by creating arrangements that share power among them. This means giving a degree of autonomy to local authorities so that territorially concentrated groups can share in decision-making power, but it also means instituting power-sharing arrangements at the central level. Often, calls for a just distribution of power and resources are not a demand simply for power from the centre but also a share in power at the centre.[10]

It should be noted that decentralisation carries its own risks – just like centralisation. There are also risks associated with post-conflict decentralisation, in particular. Libyan stakeholders raise a number of major challenges and risks associated with reforming the local governance system in Libya, in light of the current situation. These can be summarised as follows:

- Secession, division, and fragmentation – fears that greater subnational autonomy may lead to increased fragmentation, conflict between regions, and even secession in light of divisions in state institutions, the effects of the political and military conflict, and tensions between different social and political groups, particularly if large and powerful subnational units are formed.

- Social unrest – fears that opposition to some aspects of decentralisation may cause unrest and instability, particularly when it comes to sensitive issues such as the drawing of new administrative boundaries, the distribution of oil revenues, etc.

- Lack of institutional preparedness – fears that subnational authorities are not ready to exercise greater powers or manage greater resources due to:

- poor coordination between the central government and local authorities

- weak institutional capacity at subnational level – both among provinces (which currently do not properly exist as intermediary structures able to develop strategies, policies and programs at the regional level and coordinate between municipalities and the central government) and municipalities.

- a lack of skilled human resources to manage local services and resources efficiently, particularly in remote and rural areas.

- Deepening inequalities between regions – given the history of centralisation and an unequal distribution of resources between regions, several regions already suffer from significant disparities in public services and infrastructure; there is a fear these may deepen if regions are given greater powers and responsibilities, allowing better-off regions to leap ahead while leaving marginalised regions behind.

- The potential for “elite capture” at the subnational level in the event of a greater distribution of powers and resources, in light of weak oversight and accountability mechanisms – there are fears that this would lead to increased corruption, domination of some social groups at the expense of others, the creation of multiple “local autocrats” and a greater influence for armed groups.

- The fear that decentralisation may stoke social and ethnic differences, leading to local conflict and making subnational authorities unable to govern.

- The absence of sufficient revenue sources to fund central and subnational authorities in the event of a broader distribution of revenues, particularly if numerous new subnational institutions are created.

- A return to centralisation – fears that, unless agreement on expanding local autonomy and guarantees is part of a peace settlement, the “window of opportunity” for decentralisation will close, and Libya will revert to a highly centralised system.

Some Libyan stakeholders insist on the need to hold referenda to allow Libyans to have a say on the local governance system or on specific aspects of it. For instance, some stakeholders take the view that a referendum must be held on which system of government (i.e., unitary, or federal) to adopt. Some state that a future interim government should be obligated to hold referenda on local governance. Others suggest that the public must be allowed to vote on specific issues such as the proposed boundary changes for subnational units. This carries particular risks associated with referenda, such as political violence and social unrest.

3.3. Post-conflict decentralisation

Comparative experiences show that there is no empirical evidence that conclusively proves whether centralisation, unitary decentralisation or federalism are more effective in unifying divided post-conflict societies. Some countries have managed to remain intact through post-conflict federalism such as Iraq, Nigeria, Nepal and Bosnia. However, ending violence does not mean ending conflict, and many of these continue to experience deep social divisions. Furthermore, decentralisation has proven extremely hard to implement, particularly in the MENA region, due to the resistance by central governments and bureaucracies to transferring meaningful powers and resources to representative local authorities. While often raised as a slogan, many political parties and leaders may be reluctant to implement decentralisation when they face the reality that it reduces their own powers at the centre. In addition, decentralisation may be used by regional actors to exercise their own form of centralisation at the local level. As Schou and Haug note, “Decentralisation and reconciliation are both a set of institutions and legal arrangements as well as an attitude of mind…the central government both in unitary and federal states needs to compromise between centrifugal and uniting forces (ethnic groups and other groups) in order to achieve national integration.”[11]

An example of a compromise on local governance arrangements in the aftermath of conflict is South Africa. The South African constitutional system is defined by academics and experts as “unitary with elements of federalism” or “quasi-federalism.” However, the 1994 Constitution neither defines the nature of the South African state nor refers to federalism. During constitutional negotiations, the ANC strongly favoured a unitary system with a strong central state to address huge inequalities between black and white citizens. Meanwhile, some in the white-majority National Party strongly supported a federal system in the hope of establishing their own province. The Inkatha Freedom Party also strongly supported a federal system in the hope of leading their own highly autonomous province in KwaZulu-Natal where they would enjoy an ethnic majority. In the end, the parties reluctantly reached a compromise to create a form of federalism with elements of centralisation. Under this system, provinces enjoy constitutionally protected powers, and each province has an elected legislature and an executive accountable to the provincial legislature. However, the provinces are required to implement national legislation that is agreed upon nationally, and most taxation powers remain with the national government. Thus, national and sub-national governments are closely involved in each other’s functioning and share most powers and functions.

The South African example illustrates that the terms used by different groups – “federalism” and “unitary” states – are not uniform. These terms include a very broad range of options. A system can combine characteristics of federalism while being unitary, and vice versa. In addition, officially defining the local governance system using these terms may be unnecessary. Instead of focusing on terms, we recommend paying close attention to how the local governance system should practically function – which powers and resources are to be assigned to which level of government (and when and how)?[12]

3.4. How to minimise the risks associated with post-conflict decentralisation

The diversity in Libyan society, including tribal and regional affiliations, and ideological and ethnic diversity raises the question: How can the distribution of powers and resources be agreed upon in a way that might reduce conflicts and enhance social peace, national belonging, and citizenship? We suggest below a number of ways in which other countries have sought to implement decentralisation in ways that strengthen national unity.

3.4.1 Design of subnational units

The experiences of decentralisation in different countries give us some indicators about which conditions may increase or decrease conflict between groups in the context of implementing decentralisation. For example, studies show that decentralisation, especially in the form of federalism, can increase the likelihood of separatist movements emerging if local units are drawn to fit geographically concentrated ethnic groups.[13] This means decentralising power to units below that of major identity groups is less likely to fuel regionalist separatist politics. Nigeria, for example, chose to draw decentralised units that are smaller than geographically concentrated ethnic/cultural groups, to avoid this conflict risk and has managed to keep a very religiously and ethnically diverse population together.[14] Thus, no level or unit of government is associated with a particular ethnic group or religion, and local government is identified with issues of service provision rather than identity. Similarly, in Rwanda which went through a civil war in 1990-94, local districts have been drawn to combine ethnically diverse poorer and wealthier areas to promote redistribution and social cohesion.

Another choice made by some countries in order to reduce the risks of secessionism is to transfer powers to the lowest level of government, rather than the regional level. Provinces or regions, if they enjoy significant powers and resources, can become powerful actors able to challenge central government.[15] During Indonesia’s “big bang decentralisation” process, most powers transferred to subnational levels went to the sub-provincial level, and not to provinces, to minimise the risk of secessionist movements.[16] Similarly, South Africa, despite adopting a system with federal elements, also opted for an “hourglass figure” arrangement where the middle level (composed of nine provinces) shares many of its executive and legislative powers with central government, and is balanced out by municipalities with wide powers.

Another strategy used by some countries to restrict the scope for powerful subnational units to challenge the central government is to create a large number of units at the subnational level. Kenya, which experienced bouts of political violence, opted in its 2010 constitution for a large number of counties (47) to replace its previous provincial system. The counties have legislative and executive functions in a wide range of policy sectors. However, it should be noted that having a large number of subnational units may reduce their ability to be a counterbalance to central government and to prevent concentration of power at the national level.

3.4.2 Setting effective national monitoring mechanisms

In all systems, whether unitary or federal, oversight systems are needed to ensure accountability and limit the risk that local authorities may be “captured” by local elites for their own interests rather than in ways that respond to the needs of citizens.[17] National authorities may also have powers to intervene in specific exceptional situations such as bankruptcy.

We found a consensus among Libyan stakeholders on the importance of creating effective oversight mechanisms from the central to the local level, whether in an expanded decentralised or a federal system. Some emphasised the need to improve oversight of municipalities and the difficulties that exist in light of the existing divisions and conflicts. Those who support federalism proposed establishing a federal oversight body, accounting office, or monitoring agency for this purpose but some stressed the necessity of the central government not intervening except in the event of a serious violation of governance.

Therefore, effective national financial and legal oversight systems must be put in place as part of a decentralisation process. National monitoring could include establishing IT systems to collect data and measure indicators to monitor subnational governments’ progress on implementing projects and their spending (financial and output indicators.)[18] The Tunisian Ministry of Local Affairs’ program approach of introducing municipal performance indicators may be useful, in this context. Under the program, municipalities receive part of their national funding only if they fulfil certain conditions such as respecting financial procedures and reporting deadlines and involving citizens in decision-making.[19] This has the added benefit of setting objective, transparent indicators for national transfers, rather than the discretionary, opaque criteria that existed in the past. Indonesia, which decentralised in 2000, also took steps to introduce a new public finance system to replace its old outdated single-entry system. The new system introduced with decentralisation promotes transparent management of public funds, tight expenditure and financial controls with performance indicators, computerised reporting, and a tightly scheduled auditing system.

Another form of oversight is via the judiciary. In a decentralised system in which local authorities enjoy autonomy, central authorities can generally only object to subnational decisions or actions by submitting a complaint to the administrative courts. It is the courts that have the final decision as to whether to uphold a subnational authority’s decision or action depending on whether it has behaved according to the law. This raises the need to strengthen judicial institutions, particularly the administrative court, to enable it to manage an increased number of cases. Tunisia’s decentralisation reforms included the expansion of the administrative court, and the creation of 12 regional branches of the court to be able to provide decisions on disputes between different levels of government without excessive delay.[20]

3.4.3 Holding national elections before subnational elections

Research suggests that when elections are held at the subnational level in a new federal system before national elections, and where there are few nation-wide parties, this leads to greater regional divisions. In such a situation, provincial or municipal authorities may have no incentive to support the holding of national elections, since these would reduce their influence. Holding national elections first can also facilitate the preparation of the decentralisation process by putting in place a national government that enjoys the legitimacy to lead reforms.

It is also preferable, if possible, to hold regional/provincial and municipal elections at the same time, to avoid creating two subnational levels of bodies that have an interest in delaying the election of the other level. Furthermore, as regional and municipal councils may need to work together, it is better to hold elections at the same time so that both are shaped by similar political dynamics. Research has also shown that holding the elections at both these levels increases voter turnout, which can strengthen the legitimacy of the elected bodies.[21]

3.4.4 Protections for minorities

Allowing subnational authorities to override the interests of minorities in their areas can create or deepen divisions between groups and undermine national unity. Thus, decentralisation should be designed in a way that ensures protection for minorities, whether these are ethnic, linguistic, or tribal. For example, in a province that contains several tribes, each of which enjoys a majority in its area, the electoral system should be designed to ensure that all groups have adequate representation on the provincial elected body, in order to reduce tensions and resentment. Voting rules within elected councils could also be set in ways that promote inclusive decision-making rather than a “tyranny of the majority.” Minority protections could be included in the constitution and national laws and policies to safeguard minority rights nationwide and minimise grievances.

3.4.5 Require local authorities to cooperate to deliver services and share resources

There are certain types of services that are more efficiently delivered across a larger territorial area and require coordination of resources. To draw localities together and prevent them from developing isolationist or secessionist tendencies, they could be required to share responsibility for certain services, for example water.[22] Thus, municipalities could be brought closer together by giving provinces service functions such as water provision, which require coordination across several municipalities. In turn, provinces could also be required to work together by also requiring neighbouring provinces to share management of some strategic infrastructure. This could create greater interdependencies and cooperation horizontally and vertically between different authorities.

3.4.6 Strong mechanisms for intergovernmental coordination

Moving to a system of decentralisation does not mean severing ties between different levels of government. Decentralisation requires creating new mechanisms for horizontal and vertical coordination and cooperation between the different governance levels and units. These are essential for ensuring the continuity of public services and administration. Decentralisation reforms must not make public service delivery worse due to lack of coordination and/or increased conflict between different areas or different levels of government in one area.

For example, Tunisia, which introduced a new local governance law and held its first free and fair municipal elections in 2018, saw increased tensions between regional governors (appointed by the central government) and mayors (locally elected). Despite being civil servants who are supposed to be neutral, regional governors are often loyal to the individuals or political parties that appoint them, which sometimes brought them into conflict with local mayors from an opposing party or interest group. These tensions are natural in a transition from a one-party dictatorship to multi-party democracy. Under dictatorship, central-local relations were governed through a very hierarchical top-down system of orders, and coordination via a hegemonic ruling party. The move to multi-party pluralistic democracy with elected national and local governments with diverse compositions means there is a need for greater negotiation and bargaining between the different levels of government, which represent different territorial and political interests.

The problem is that the 2018 Local Authorities Code did not specify how exactly the governorate, regions and municipalities should work together. It left this issue to be determined later in an executive decree, but this was never issued due to delays. If the decentralisation process does not create institutional mechanisms for the effective negotiation and mediation of different interests in a collaborative way, this can lead to the obstruction and even paralysis of local services.

Creating vertical and horizontal coordination mechanisms is particularly important in divided countries such as Libya where, even after the end of a war, there is a significant risk for conflict between different areas/groups. If Libyan actors want decentralisation and local governance to deliver concrete benefits for citizens including improved services across Libya, it is essential to think closely about how to establish a local governance system in which there is a balance between local autonomy and intergovernmental coordination and coherence. It is important to think about decentralisation – whether in a unitary or federal system – not as a central vs. subnational relationship or a process merely of dividing responsibilities, powers, and resources, but of redesigning the coordination between central and subnational authorities. Such interaction will require operational mechanisms to make it work effectively, for the benefit of citizens.

These mechanisms are usually created and operated within specific policy sectors, e.g. health, education, transport. For example, Brazil, a federal country that decentralised following the Constitution of 1988, reshaped its decentralisation model by creating more intergovernmental coordination mechanisms between central government, states, and municipalities in order to deliver services such as health, education and social welfare. For instance, the 1988 Constitution enshrined the right to free healthcare. A system was put in place in which the federal government set national standards and monitoring systems, and the municipalities managed parts of the healthcare system. During the 1990s, the Health Ministry published the National Basic Operating Standards (NOBs) and the Basic Care Minimum Standard on health and drew up a universal health care system. Under the system, the federal state would be responsible for tertiary health care, while municipalities would deliver primary health care. The two levels shared responsibility for secondary care between them. The federal government was responsible for funding the system. To join the system, municipalities had to fulfil institutional and administrative conditions to show that they had the necessary management capacity. It took around seven years (1991-98) for all municipalities to join the universal health care system. Municipalities received automatic regular transfers to fund the healthcare based on clear and transparent criteria (such as the number of inhabitants). The federal Health Ministry monitors the program through data systems.

In order to ensure intergovernmental coordination, the federal government created a whole set of federative coordination forums that involve municipal, state and federal managers in making decisions on national health policy, including the Tripartite and Bipartite Inter-manager Commissions, which are part of the National Council of Municipal Health Departments (CONASENS) and the National Council of Health Secretaries (CONASS). These are new spaces of intergovernmental negotiation that were not envisaged by the 1988 Constitution but evolved over time. to respond to the real need for coordination between. Problems remain and disputes occur between different levels of government, but the system has allowed for the delivery of basic health services to citizens.

The Brazilian example of intergovernmental coordination is important because it highlights how local governance reforms need to consider how to give local authorities autonomy while maintaining close interaction and constant coordination between different levels of government. Decentralisation must not be seen as being about creating autonomous islands of authority within a state. This will not work, neither for subnational units nor for citizens. Furthermore, decentralisation does not mean weakening the central state. As the Brazilian example shows, it requires strengthening the central state’s capacity to regulate and direct policies and programs, while allowing subnational authorities a greater role in decision-making and implementation. Failing to think about complementarity and coordination between different levels risks weakening services, which may cause citizens to experience decentralisation negatively, rather than enjoy its benefits.

Conclusion

Libya’s system and history of local governance and its particular social, historical, political, and institutional specificities call for a comprehensive analysis and dialogue in order to find a political and administrative system that is compatible with the aspirations of the Libyan people for freedom, dignity, and well-being, and the use of the country’s vast capabilities, opportunities, wealth, and diversity.

Decentralisation requires the sharing of powers and resources between the centre and subnational authorities that enjoy administrative and financial independence within the framework of the Constitution and the law, as the structures closest to citizens, most familiar with their problems, and most capable of finding solutions and rapid intervention.

As mentioned above, decentralisation is not a zero-sum game between central and subnational authorities. Nor does it mean the dismantling or withdrawal of the central state from its responsibilities. Successful decentralisation requires strengthening the capacities of both central and local government, while changing their distribution of roles and modes of interaction away from a hierarchical relationship towards greater coordination, cooperation, and complementarity. It also requires strengthening judicial and administrative systems and extending their presence throughout the national territory to enable subnational authorities to function well.

Decentralising while maintaining Libya’s territorial unity will require situating local governance reforms within a broader framework focused on state building, reconstruction, and national reconciliation. This will need to include a number of strong integrative mechanisms that minimise the risks of fragmentation, as outlined in the paper. An important step that can pave the way for linking the idea of strengthening local governance to national reconciliation is to involve local councils in national reconciliation efforts, building on the local reconciliation processes that have occurred in past years. [23] Involving local authorities in solving key post-conflict issues such as reintegrating former fighters could also help build the legitimacy of these bodies and their ability to resolve conflict and build local social cohesion.

Decentralisation certainly carries a number of risks and challenges in light of Libya’s existing state of division and fragmentation, socially, politically and institutionally, as outlined above. However, strengthening local governance through some form of transfer of powers and resources from the centre to the subnational level will be essential under any future system of government that seeks to rebuild the legitimacy of the state and respond to deep public grievances associated with regional inequalities in access to services and infrastructure. Deciding on what form this system should take will require a process that brings together key local power brokers, who must see an interest for themselves in engaging in a nationwide institution-building process and in keeping Libya together rather than in dividing it.

Bibliography

[1] Throughout the paper, the term “local authorities” will be used to refer collectively to all subnational authorities (i.e. this includes regions, provinces, municipalities, districts, etc.).

[2] For example, Decision No. 154 of 2021 by the Minister of Local Governance on provisions regarding the organisational structure of the Municipal Guard, which stipulates that the branches of the Municipal Guard and their employees are subject to the direct supervision of the Mayor of the Municipality.

[3] CILG-VNG International, The Situation of Decentralisation and Local Governance in Libya, 2022, available at https://www.cilg-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/A33-The-situation-of-Decentralisation-and-Local-Governance-in-Libya.pdf

[4] قرار رقم 171 لسنة 2021 م بإصدار

[5]. Decision No. 330 of 2021 regarding the regulation of local revenues

[6] For more on local and municipal finance, see “Generating Municipal Financial Resources: A Brief Guide for Libya’s Municipalities,” Economic Growth Practices in Asia and the Middle East Project, USAID, 2016; and “Libyans Rebuilding Libya: Best Practices in Local Governance,” Libyan Expertise Forum for Peace and Development, 2021.

[7] In addition, it is reported that some municipalities are collecting some taxes, even if this is not clearly legal.

[8] In 2022, Resolution No. 182 of 2022 was issued to establish and organize provinces, stipulating the establishment of 18 provinces, but according to available information, this decision has not been implemented yet.

[9] Law No. (9) of 2013 AD, which amended Law No. (59) of 2012 AD regarding the local administration system, stipulates that the powers assigned to the provincial council shall be exercised by the municipal council and the mayor, until the provinces and their councils are established, with the exception of some powers, which shall be exercised by the Council of Ministers.

[10] Power-sharing arrangements at the central level are a separate theme that will not be addressed in this paper, since it focuses on decentralised multi-level governance. However, it will also be a critical one to address in conjunction with discussions on a future decentralised model.

[11] Arild Schou, and Haug, M., “Decentralisation in Conflict and Post-Conflict Situations,” Working Paper No. 139, Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research, 2005.

[12] These questions are discussed in greater detail in the paper on the distribution of functions, within this same series.

[13] Jean-Paul Faguet, Fox, Ashley M. and Poeschl, Caroline (2014), “Does decentralisation strengthen or weaken the state? Authority and social learning in a supple state”, Department of International Development, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK; Gareth J. Wall (2016), “Decentralisation as a post-conflict state-building strategy in Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Sierra Leone and Rwanda”, Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 1:6, 898-920.

[14] Rustad Siri Aas, “Between War and peace: 50 years of Power-sharing in Nigeria”, CSCW Policy Brief, 6. Oslo: PRIO, 208; Osaghae, E., “Ethnic Minorities and Federalism in Nigeria,” African Affairs, Volume 90, Issue 359, April 1991, pp. 237–258.

[15] Ricart-Huguet, Joan and Sellars, Emily, The Politics of Decentralisation Level: Local and Regional Devolution as Substitutes (July 12, 2021). World Politics, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3885174 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3885174

[16] Except for Aceh and Papua, in which there were armed secessionist movements in the past.

[17] Pranab Bardhan, Mitra, S., Mookerjee, D., and Sarkar, A. (2008). “Political Participation, Clientelism, and Targeting of Local governance Programs: Analysis of survey results from rural West Bengal, India,” Boston University – Department of Economics – The Institute for Economic Development Working Papers Series dp-171, Boston University – Department of Economics; James Manor, The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralisation (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 1999).

[18] Italy, for example, has a national monitoring system that uses an open data approach, to strengthen public trust and combat corruption – https://opencoesione.gov.it/en/

[19] World Bank, “Tunisia: Urban Development and Local Governance Program”, available at https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P167043

[20] Justice Administrative Tunisienne, available at https://www.jat.tn/fr/article/cr%C3%A9ation

[21] Enrico Cantoni et al., “Turnout in concurrent elections: Evidence from two quasi-experiments in Italy”, European Journal of Political Economy, Volume 70, December 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102035

[22] In large, rural or sparsely populated regions, it might be advisable to give provinces responsibility for most or all services and functions.

[23] In Sierra Leone, for example, local councils took decisions and issued regulations on the reintegration of former fighters, as well as holding reconciliation and community cohesion sessions.

In focus

Subnational Governance in Divided Societies: Learning from Yemen to Inform Libya’s Peace Process

MRAD, Mohamed Aziz

8 January 2026

Youth as Catalysts for Shaping Libya’s Future Pathways for Inclusion in National Dialogue and Vision -Making

SKOURI, Abdelkarim

2 December 2025

Hydrogen Valleys and Sustainable Development in Algeria: Pivoting from Hydrocarbons to an Inclusive Euro Mediterranean Hydrogen Economy

STILLE, Leon

21 November 2025