EastMed and the Geopolitics of Connectivity - Energy, Diplomacy, and Regional Cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean

Abstract

The Eastern Mediterranean has emerged as a focal point of energy geopolitics, with natural gas discoveries offering both opportunities for cooperation and sources of tension. This paper examines the role of energy diplomacy and connectivity-driven initiatives, assessing both the EastMed pipeline and the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) as mechanisms for regional engagement. While EastMed was envisioned as a key infrastructure project for integrating Mediterranean energy markets, its geopolitical and economic feasibility remains highly uncertain. Instead, the EMGF, if restructured and made more inclusive, holds greater potential as a platform for regional coordination, enabling transactional agreements that could foster broader diplomatic engagement. This study argues that energy infrastructure should be viewed not as isolated projects but as part of a connectivity-based approach, where economic cooperation lays the foundation for long-term regional stability. Ultimately, inclusive energy governance could transform the region from a zero-sum geopolitical battleground into a zone of gradual economic and political convergence.

1. Introduction

As instability in the Levant looms in the wake of the Gaza War and amidst ongoing regional crises, it is imperative to devise new paths that could lead to rapprochement between the regional actors. Despite long-standing rivalries and geopolitical tensions, countries in the Eastern Mediterranean can find common ground through economic cooperation, laying the foundation for addressing broader political issues. If properly managed through a well-designed, win-win cooperation strategy, the exploitation of regional natural gas resources could help untangle rivalries and foster economic and political connections among not like-minded actors.

Before the escalation of violence and tension started with the October 7th attacks, diplomatic efforts in the broader Middle East and North Africa region had been leading to a series of rapprochements, a product of shifting socio-economic factors and geopolitical alignments.[1] Despite the renewed conflict, some of the progress previously achieved continues to hold, suggesting that the fragile détente has not been entirely undone. This leaves open potential avenues for dialogue among the regional actors, which could open the way to diplomatic normalization in the Eastern Mediterranean. Broad economic cooperation, especially for countries facing severe financial constraints and seeking to bolster their economies, can serve as the first step toward a possible new equilibrium. Central to this is the recognition that natural gas exploitation can act as a key driver for collaboration.

This strategy of economic cooperation is deeply intertwined with the concept of “Connectivity”[2] based on the development of physical infrastructures, such as transportation hubs – pipelines, railroads, ports – and their linkage with a “connectivity of people”. A connectivity strategy can often lead to the creation of regional alignments, emphasizing the role of deliberate policy design in strengthening collaboration and shared development within and between regions.[3]

A connectivity strategy would rely in creating links—economic, infrastructural, and human—that promote cooperation without dragging into excessive interdependence. A win-win approach ensuring shared benefit, avoiding debt traps, network domination or power imbalances.

This policy paper explores the geopolitical, economic, and strategic significance of energy cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean. It first examines regional energy geopolitics, focusing on the EastMed pipeline’s feasibility, geopolitical challenges—particularly Turkey’s role—and the role of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) in either fostering cooperation or exacerbating tensions. The second section assesses the EastMed project’s viability amid regional conflict, shifting U.S. policies and global energy trends. Finally, the paper explores connectivity statecraft, arguing that a more inclusive EMGF could enhance regional integration, economic development, and long-term stability.

2. Energy Geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean

2.1. The EastMed Project

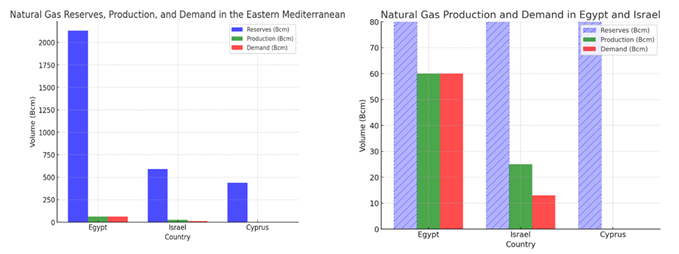

Natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean, although relatively small on a global scale – around 3.5% of MENA’s reserves[4]– has a considerable impact on the regional equilibrium. This is because a major amount of the gas fields lies under the seabed non yet exploited. The reserves are distributed across several countries, each with varying levels of development. Egypt boasts the largest reserves in the region, estimated at 2.13 trillion cubic meters (tcm), with a production that reaches only around 60 billion cubic metres (bcm) a year, an amount barely enough to meet its internal demands. Israel follows with approximately 0.59tcm with a production capacity of 25bcm and only about 14bcm of demand, giving the country the possibility to export its surplus.[5] On the contrary Cyprus’s reserves are estimated at 0.11tcm and are yet to be developed, while Lebanon’s and Palestine’s – offshore of the Gaza strip – reserves are still to be accurately quantified.[6] It is clear from this picture that these countries have much room for development of natural gas production and export.

Source: Natural gas reserves, production and demand in the Eastern Mediterranean. (Source: Bowden & Golan, prepared by the author)

The presence of natural gas in the Levantine seas presents a potential avenue for economic development. Yet, whether these reserves can translate into long-term economic benefits remains an open question, heavily dependent on regional cooperation, global market conditions, and infrastructure challenges.

If effectively extracted and commercialized, natural gas can stimulate economic growth in multiple ways. Following the Ukraine war, rising oil prices provided fiscal relief for struggling MENA economies.[7] A similar dynamic could apply to natural gas, potentially providing gas-producing countries with a stable and much-needed influx of foreign currency. As a capital-intensive sector, natural gas also has the potential to attract FDI and create new jobs in extraction, transportation, and processing industries. Beyond direct revenue generation, energy infrastructure projects could stimulate larger economic clusters, reinforce industrial development, and enhance energy security for producer countries.

Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus have already established an energy triangle, engaging in mutual gas trade that has strengthened their energy interdependence.[8] However, as Huurdeman from the World Bank suggests, the true game changer for the Levant would be the ability to export large volumes of gas to Europe, transforming the regional market into a global one.[9]

The major obstacle to the development of this resource is not technical but political. The Eastern Mediterranean is an area where not like-minded countries try to obstruct each other or claim rights over a resource rich zone. Some of these rivalries are historically entrenched, such as the long-standing dispute between Turkey and the Republic of Cyprus, with the island remaining divided since the Turkish military intervention in 1974. Others are more dynamic, exemplified by the fluctuating relationships between Israel and its neighbouring states.

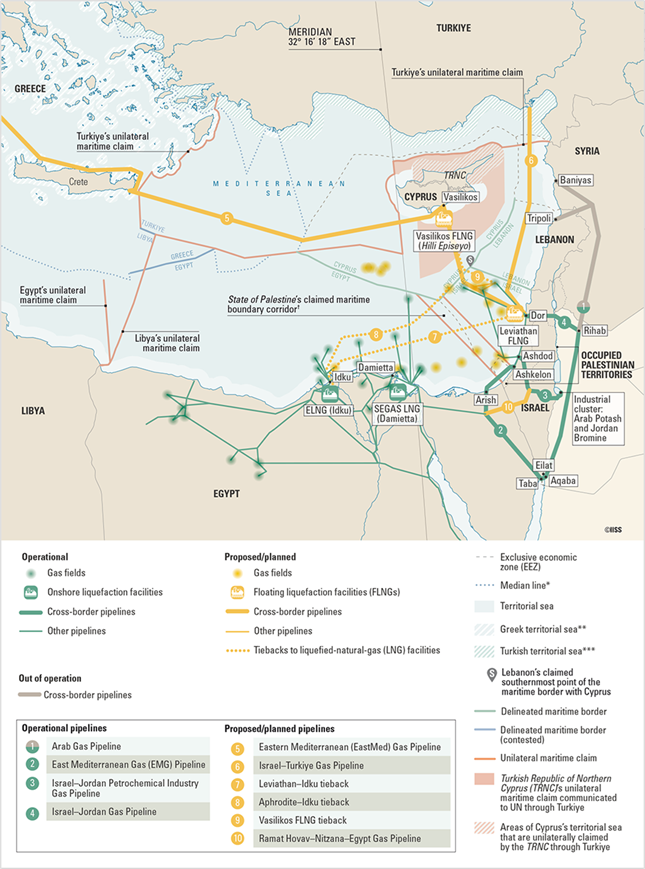

Moved by the opportunities provided by the possibility to export local natural gas surplus to the EU market, some European companies in the first years of 2010s developed the EastMed pipeline project. The project, now a 50-50% joint venture between EDISON and DEPA[10], aims to connect the Eastern Mediterranean fields to mainland Europe, providing a direct route passing through Israel, Cyprus, Crete and Italy.[11] The pipeline would be capable of transporting from 12 to 20bcm per year and has been assessed as feasible and cost-effective by the risk management firm DNV in 2022.[12] It was initially welcomed by many stakeholders and attracted interest from the EU, which, as early as 2013, included it in its Projects of Common Interest list. However, the EastMed has remained unrealized due to multiple factors. One key reason is that, at the time, potential buyers were primarily sourcing inexpensive natural gas from Russia.[13] Additionally, the region has historically been, and continues to be, politically unstable, with deep-seated geopolitical rivalries that have hindered regional development.

The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has profoundly reshaped the EU’s energy priorities, compelling Member States to reduce and then phase out reliance on Russian supplies.[14] This shift has reignited discussions on EastMed at both the governmental and academic levels, with growing interest in its potential role in Europe’s energy diversification strategy. Yet, several key obstacles to its development persist. In addition to the political risks created by the volatile and conflict-prone region, opposition from major regional actors, particularly Turkey, continues to be a significant challenge. Furthermore, technical and market related concerns recently arose.

2.2. Geopolitical Roadblocks: The Role of Turkey and the ‘Blue Homeland’ Doctrine

Since its inception, the EastMed project has been hindered by geopolitics. The opposing interests of key actors have so far prevented the political consensus needed to build the shared infrastructure required for its development. With a capacity of up to 20bcm, the EastMed pipeline holds the potential to provide substantial economic benefits to the countries —primarily Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus22and partner companies.

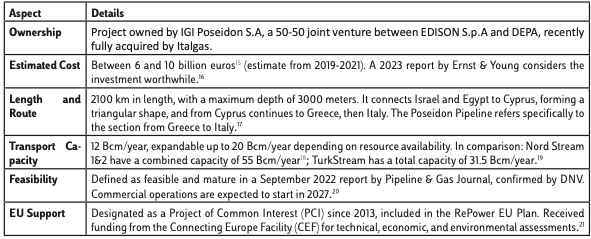

A fundamental geopolitical issue has been the exclusion of Turkey from the project. In 2013, an Israeli conglomerate of firms entered advanced talks with Turkish counterparts to build a pipeline exporting gas to Europe. However, given the already strained relations between the two countries the negotiations stalled —particularly since the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, in which Israeli forces raided a Turkish ship bound for Gaza, resulting in the deaths of nine Turkish citizens.[23] As new gas discoveries were made in the waters of Cyprus and offshore Egypt, these three countries – all of which had tense relations with Turkey – began forming partnerships, effectively leaving Turkey out of any initiative.[24]

This exclusion further deepened regional tensions, particularly on the ongoing dispute over Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) in the Mediterranean, with Turkey and the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus claiming right over areas internationally recognized as belonging to Greece or the Republic of Cyprus. Turkey never ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as Article 121 grants islands their own economic zones, which, would deprive Turkey of a significant portion of its claimed waters. Instead, Turkey, following a controversial legal approach,[25] Turkey bases instead its claims on the concept of the continental shelf.[26]

Following the ‘Blue Homeland’ (Mavi Vatan) doctrine,[27] to assert its claims over the legally disputed EEZ the Turkish Navy carried out several aggressive actions between 2018 and 2020. This approach, described as a modern form ‘Gunboat diplomacy’ aimed at expanding Ankara’s influence in the Mediterranean.[28] In 2018, Turkish military exercises forced the Saipem 12000 vessel to halt drilling operations in Cypriot waters due to safety concerns.[29] A similar approach was followed in 2019, when Turkish drill ships Yavuz (Inflexible)[30] and Fatih (The Conqueror)[31] conducted exploratory drillings in the same contested waters. In August 2020, tensions peaked when the Greek Navy frigate HN Limnos and the Turkish one TCG Kemal Reis collided.[32] Even though events of the same magnitude as those in the past have not occurred in more recent years, the Turkish government’s statements make it clear that Ankara remains committed to pursuing its claims in the Eastern Mediterranean. In particular, the Minister of Energy, Alparslan Bayraktar, stated in August 2024:

“We have never given up on the Mediterranean. Unlike some, we do not see the Blue Homeland as a mere fantasy. God willing, the Blue Homeland will be our epic in these seas.”[33]

It is clear from this pattern that the Turkish government, might respond aggressively whenever feels that its interests are at stake, creating a zero-sum game and hindering the development of EastMed.

Figure. Eastern Mediterranean gas landscape. (Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), 2023)

2.3. The EMGF – Bridging or Dividing? Struggle for Regional Energy Cooperation

Geopolitical roadblocks have not only stalled the EastMed pipeline but have also partially hindered the broader development of natural gas in the region. To institutionalize cooperation and create a structured policy dialogue platform on natural gas, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan and Palestine established in 2019 the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF). Based in Cairo the EMGF is an international intergovernmental organization that brings together diplomats and stakeholders. Its main governing body is the ministerial committee, composed of the ministers in charge of energy affairs. The forum aims to address geopolitical and economic challenges and facilitate agreements on shared energy projects, including the EastMed pipeline.[34]

The EMGF could, in theory, play an important role for dialogue, among the forum’s successes, it managed to bring together two historically hostile parties, Israel and Palestine—an achievement that initially received little attention and the significance of which is now debatable. Additionally, the prospect of EMGF membership may have played a role in encouraging the maritime delimitation agreement between Israel and Lebanon in 2022.[35]

However, despite its regular ministerial meetings, its ability to produce tangible outcomes remains, to date, rather weak. While the forum continues to hold high-profile gatherings and participate in international energy conferences, these engagements have yet to translate into concrete agreements.[36] The EMGF has largely failed to make significant strides in fostering deeper collaboration or advancing infrastructure projects. The reasons for its lack of impact include the competition from other fora, such as the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) and the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), the prevalence of bilateral agreements, an imprecise statute, and the absence of a rigid framework of binding legal obligations for its members.[37]

Yet, as most of the analysts argue, the major factor impacting its unsatisfactory performance, resides in the forum’s “undeniable geopolitical dimension”: instead of acting as a neutral coordination platform, the EMGF reflects the existing political alignments of its founding members, particularly Greece, Cyprus, and Egypt.[38] It deliberately left out Turkey, one of the most geopolitically and economically active players in the Eastern Mediterranean. This exclusionary approach has prevented the forum from achieving its intended role as a mediator in regional energy disputes.[39]

From Ankara’s perspective, the EMGF and the EastMed pipeline are part of a containment strategy designed to marginalize Turkish interests.[40] In response, Turkey has pursued unilateral energy exploration, expanded its Blue Homeland doctrine, and challenged maritime boundaries through its own agreements, particularly with Libya.[41]

Despite its assertive stance, Turkey has shown periodic openness to dialogue. In September 2024, during a visit of the Egyptian President Al-Sisi in Ankara the Turkish President Erdoğan expressed the desire to improve cooperation in the natural gas sector.[42] Former Energy Minister Berat Albayrak, in his roadmap-book Burası Çok Önemli, published in 2022, emphasized that Turkey is willing to discuss shared economic benefits, provided that its sovereign claims and strategic interests are acknowledged. Albayrak highlighted the potential of energy cooperation as a tool for stability in the Eastern Mediterranean, stating:

“We and the Israeli side emphasized the significant potential of energy resources in ensuring peace and prosperity in the Eastern Mediterranean basin.”

He also stressed that Turkey was open to constructive dialogue with Egypt and the need for a mutually beneficial resolution to the Cyprus issue:

“Following Israeli gas, we discussed dialogue with Egypt, resolving the Cyprus issue in a way that benefits all sides, and including the natural gas of both countries in a planned infrastructure between Israel and Turkey.”

He also warned that “pursuing routes without Turkey” is unsustainable, a prediction that has so far proven accurate.[43]

While Turkey is unlikely to abandon its maritime claims, in recent years, it has shown a willingness to negotiate, suggesting that a more inclusive regional approach could be feasible. A phased approach could provide a viable path forward, allowing for gradual cooperation while addressing political and economic challenges.

Many authors have suggested that taking incremental steps toward broader inclusion could help make the EMGF more effective. In a 2023 interview, Edison CEO Nicola Monti highlighted that: “a link between Israel and Cyprus can be a first portion of the EastMed pipeline we are promoting,” further suggesting that additional connections could later be developed to link Cyprus’s facilities to mainland Europe.[44] Similarly, Alexander Huurdeman, a senior gas specialist at the World Bank, advocates for a top-down approach, expanding the EMGF to as many countries as possible through a phased strategy. He emphasizes that “cooperation is the decisive factor” in making regional natural gas exploitation economically viable—though he does not explicitly mention Turkey.[45]

A practical first step would be establishing extraction and connection facilities between Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus— what could be termed as the “Natural Gas Triangle.” This phase would ideally include discussions with Turkish representatives. However, discussions have stalled due to regional instability and the Gaza war, but a May 2024 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies paper still sees this as the best starting point when conditions will allow.[46]

The EMGF was established to foster regional energy cooperation, yet its exclusionary approach has prevented meaningful progress. Instead of bridging geopolitical divides, the forum has reinforced existing tensions, limiting its ability to facilitate agreements. For the EMGF to fulfil its mission, it must evolve into a more inclusive platform.

3. New Landscapes of the Levant

3.1. Is EastMed at a Dead End?

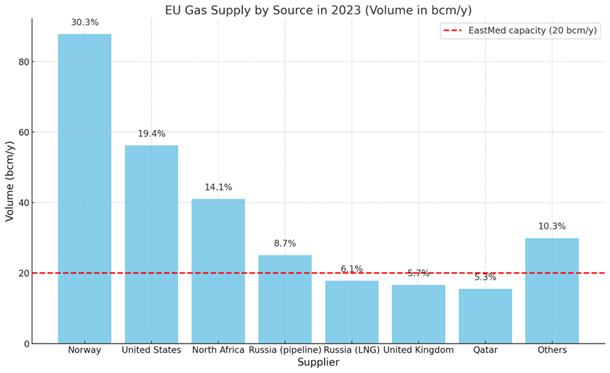

While the potential for regional gas development remains substantial, longstanding disputes over EEZs, regional rivalries, and fluctuating market dynamics have presented persistent obstacles. However, recent developments have further reshaped its prospects, making its future uncertain but not entirely foreclosed. As mentioned, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, European countries intensified their search for alternative energy sources, briefly reviving discussions on EastMed. Some analysts supported the expansion of economic corridors with the EU’s southern neighbourhood to reinforce supply chains,[47] and the pipeline was once again included in the EU’s Projects of Common Interest (PCI) list, which benefit from expedited procedures and, in certain cases,co-financing through the Connecting Europe Facility.[48] On the other hand, this renewed attention coincides with a broader shift in EU energy policy—the Green Transition. As the bloc phases out natural gas and invests more heavily in renewables, the long-term strategic relevance of EastMed is increasingly questioned. While the EU still supports the project on paper, its commitment must be weighed against its decarbonization goals and the decreasing role of fossil fuels in its energy mix.

Beyond the EU’s shifting stance, EastMed’s feasibility also depends on the capabilities of regional gas producers. Egypt, the country expected to play a central role in exporting Levantine gas to Europe, is now facing major production challenges. Reports from consulting firms RBAC, a provider of gas and LNG market simulation systems, and BMI, a risk management company, indicate a decline in gas production, with Egyptian LNG exports diminishing compared to previous years[49]. The country, struggling to meet domestic gas demand has shifted focus from exports to internal consumption, and the sale of its two[50] FSRUs (Floating Storage and Regasification Units) has further limited its capacity to import LNG, leaving it increasingly dependent on internal production and Israeli gas imports via pipeline.

While Egypt’s top gas fields have sufficient reserves to meet forecasted consumption, recent reports suggest production is declining due to water infiltration issues in the Zohr field—its biggest. The government has disputed these claims, pointing to a $15 billion investment in gas fields over the next three years to sustain output and prevent shortages. However, the overall situation, quoting BMI, “paints a bearish outlook for the country’s long-term gas production.”[51] As Egypt – the largest gas producer in the Eastern Mediterranean – struggles to maintain steady production, the feasibility of using EastMed as a stable export corridor becomes more complex.

Other regional producers face their own challenges. Cyprus, despite its offshore discoveries, has yet to begin large-scale production, though a February 2025 agreement with Egypt aims to facilitate liquefaction and re-export of Cypriot gas to Europe.[52] Lebanon’s energy sector remains paralyzed by political instability, tensions between Israel and Hezbollah, and a deep financial crisis that deters foreign investment.[53] These factors collectively place the EastMed pipeline project in a precarious position.

Compounding these economic and technical issues is the impact of the October 7, 2023, attacks and the subsequent war in Gaza, which have significantly disrupted regional energy cooperation. As Valbjørn et al. argue, the war has “taken the region ‘forward to the past’ by revitalizing ‘Palestine’ as a central issue.”[54] The ongoing conflict has halted regional cooperation efforts, deterred investors, and escalated tensions between Israel and its neighbours, further reducing the likelihood of diplomatic breakthroughs in the energy sector.

Given the scale of the crisis, any meaningful progress on EastMed is unlikely in the short term. However, it is worth considering whether diplomatic engagement could eventually resume. Before October 7th, there were signs of regional rapprochement, and some of them have not been entirely severed.Egypt still maintains very strong economic ties with Israel, ties on which its energy supply depends.[55] The Abraham Accords, signed in 2020 between Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain (later joined by Morocco and Sudan), had begun reshaping diplomatic and economic relations in the region, setting a precedent for cooperation between Israel and Arab states. While these agreements have not yet expanded further, they remain in place, providing a potential framework for future diplomatic engagement.

Even Turkey, which has historically opposed the EastMed pipeline, recently restored ties with Egypt after years of estrangement. Although President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has adopted increasingly aggressive rhetoric towards Israel, warning in July 2024 that “We entered Karabakh, we entered Libya, and we can do the same elsewhere. Nothing is stopping us, as long as we are strong,”[56] these statements have not yet translated into any direct action. Instead, they appear primarily aimed at domestic and regional audiences, reinforcing Turkey’s strategic position without triggering escalation. This suggests that, while tensions remain high, Ankara’s approach still leaves room for pragmatic engagement.

While these factors are currently overshadowed by the ongoing conflict, they indicate that once stability returns, there may be opportunities for energy diplomacy to resume. The Gaza war has effectively placed regional negotiations on hold, but it has not eliminated the underlying economic incentives for cooperation. A post-war diplomatic reset could create space for renewed discussions, but the pipeline’s future will depend on whether the regional players are willing to overcome political divisions in favour of the possibility of long-term economic gains.

3.2. U.S. Policy on the EastMed Pipeline

American policy toward the EastMed pipeline has shifted significantly over the years, reflecting broader changes in U.S. strategic priorities. Under the first Trump administration, Washington supported the initiative, viewing it as a way to distance the EU from the Russian energy market and believing that the prospect of shared profit for the coastal countries would push them to cooperate rather than compete.[57] However, in January 2022, the Biden administration announced a policy reversal, withdrawing its support for EastMed. The decision was based on three key factors. First, the new administration favoured green energy projects. Secondly, the project’s economic viability was increasingly questioned. Finally, concerns arose on the regional tensions it generated. This decision took Israeli and some American officials by surprise, as there was a lack of consultation with the governments of Cyprus, Greece, and Israel.[58]

Other analysts have suggested additional strategic considerations. As early as 2022, the research centre SETA – Siyaset, Ekonomi ve Toplum Araştırmaları Vakfı, allegedly close to the Turkish government – argued that the U.S. withdrawal could also be linked to Washington’s interest in expanding its own natural gas exports to Europe.[59] This perspective has gained further relevance as the EU is increasing its reliance on American liquefied natural gas. U.S. LNG exports to Europe surged from 18.9 bcm in 2021 to 56.2 bcm in 2023, accounting for 19.4% of total EU gas imports.[60] With the possibility of another policy shift under a second Trump administration, it remains uncertain whether the U.S. stance on EastMed will change again. Yet, given the strong position of American LNG in Europe, Washington has little economic incentive to support a competing supply route.

3.3. Connectivity Opportunities

Unlocking the full potential of the Eastern Mediterranean’s natural gas resources has long been hindered by various factors, the most significant being the lack of cooperation among the coastal nations of the Levant. Whether in terms of infrastructure development or the establishment of trade routes, geopolitical competition and zero-sum thinking have obstructed progress. However, connectivity-oriented cooperation, driven by economic incentives, could offer a pathway forward.

As Yair Lapid, then Alternate Prime Minister of Israel, stated in his 2022 Foreign Affairs article, “Governments can cooperate in some areas even when they disagree, compete, or clash in others. In this way, if we work correctly, we can build new kinds of ties and alliances, ones that we haven’t seen before. I call this path Connectivity Statecraft.”[61] He added that countries should organize their partnerships, “according to subject, not regime type.”[62] This would allow the implementation of connectivity strategies between not like-minded actors, as long as those are win-win strategies. In the case of EastMed, this principle could allow countries to build trust through energy cooperation, despite broader political disagreements.

The East Mediterranean Gas Forum already serves as an institutional framework for regional energy dialogue, bringing together multiple Mediterranean actors. However, for both EastMed and the EMGF to succeed as long-term connectivity initiatives, they must adopt a more inclusive approach and survive the current period of turmoil.[63]

At the same time, EastMed should not be conceived solely as a pipeline but as part of a broader, networked energy infrastructure. This includes LNG terminals, electricity interconnections, and renewable energy projects—all of which can reinforce economic interdependence while diversifying the region’s energy landscape. A network-based approach would enable the EMGF to evolve into a genuine Mediterranean energy cooperation platform, integrating not only regional gas producers but also transit states and emerging renewable energy hubs.[64]

However, connectivity must be approached carefully. Scholars Daniel W. Drezner, Abraham L. Newman, and Henry Farrell (2021) have introduced the concept of “weaponized interdependence”[65], referring to the way economic and technological linkages can be exploited as tools of geopolitical coercion. Mark Leonard’s Age of Unpeace expands on this, highlighting how connectivity has increasingly been leveraged as a means of hybrid warfare, including trade disruptions, infrastructure manipulation, and weaponization of migration flows as geopolitical tools.[66]

The Mediterranean’s geostrategic importance makes it particularly vulnerable to such “connectivity wars.”[67] Disruptions in gas supply chains, port operations, or energy transit routes – it’s enough to mention how so-called Houthis “torment global trade” since 2023[68] – could have severe geopolitical consequences, reinforcing uncertainty rather than fostering stability.[69]

To mitigate these risks, the EU’s Global Gateway initiative has promoted an approach that advocate to “forge links, not create dependencies.”[70] This principle is particularly relevant in the Eastern Mediterranean, where energy relations are increasingly shaped by a “triangle of interdependencies”[71] between Israel, Egypt, and Cyprus . Egypt’s growing reliance on Israeli gas, Cyprus’ dependence on Egyptian LNG terminals, and Israel’s need for stable export routes all illustrate how mutual energy reliance can drive cooperation—but also create vulnerabilities if mismanaged.[72]

Thus, a more inclusive and strategic vision for the EMGF and EastMed is necessary. Prioritizing connectivity over exclusion could help transform the Eastern Mediterranean from a zone of competition into one of shared economic and energy interests. Instead of reinforcing geopolitical divides, the EMGF should actively seek to integrate regional players, including Turkey. By adopting a networked, multi-layered approach to energy infrastructure, the Mediterranean can avoid weaponized interdependence while laying the groundwork for a more resilient, cooperative, and integrated regional energy landscape.

4. Conclusions

The EastMed pipeline has long been envisioned as a tool for regional energy cooperation, yet its implementation remains uncertain due to deep-rooted geopolitical tensions, economic constraints, and shifting energy policies. While technically feasible, the project faces significant challenges, including competing national interests and unresolved maritime disputes. Given these obstacles, its long-term viability is questionable, making it less likely to serve as a practical means of fostering regional integration. However, the broader framework of energy diplomacy in the Eastern Mediterranean does not solely depend on EastMed.

One of the central arguments of this paper is that energy cooperation in the region must begin with transactional agreements brokered through forums like the EMGF, gradually fostering trust and creating pathways for broader dialogue. By aligning economic interests, these initial exchanges can provide a foundation for addressing larger geopolitical and social challenges.

Yet, the exclusionary nature of the EMGF and Turkey’s persistent marginalization have deepened regional divisions rather than fostering cooperation. A more inclusive approach – one that recognizes Turkey’s strategic position and seeks pragmatic engagement – could shift the dynamics from confrontation to collaboration. Including Turkey in the EMGF would signal a significant gesture of openness from its historical rivals and could facilitate the establishment of EEZs in the Eastern Mediterranean through bilateral agreements, a growing trend among Mediterranean states. Without even a partial agreement on EEZs, progress on both the EastMed project and Cyprus’s natural gas development would remain stalled, likely prompting Turkey to take assertive measures to protect what it perceives as its vital national interests.[73]

While EastMed faces uncertain prospects, the EMGF offers a more viable and adaptable framework for regional cooperation. Unlike a single infrastructure project like the EastMed pipeline, the EMGF is an active institution capable of facilitating dialogue, mediating disputes, and promoting pragmatic energy agreements. By emphasizing a phased approach – where economic collaboration lays the groundwork for political engagement – it can serve as a structured platform for connectivity-driven diplomacy, ensuring that energy resources contribute to stability rather than fuelling conflict. Given its institutional nature, the EMGF is better positioned to sustain engagement and advance economic diplomacy in the region.

A key strength of the forum lies in its dual role as a platform for South-South cooperation among regional actors and North- South collaboration with the EU. To ensure its long-term relevance, the EMGF should broaden its focus beyond natural gas, integrating renewable energy initiatives in alignment with the EU’s decarbonization goals. Expanding its agenda in this way would not only enhance regional energy security but also reinforce its role as a leading forum for sustainable energy collaboration in the Mediterranean.[74]

The broader energy landscape in the Levant remains highly sensitive to local political shifts, with the ongoing war in Gaza being the most immediate factor disrupting regional dialogue and halting joint infrastructure investment projects. While discussions with Israel may eventually resume once tensions ease, the country must navigate these negotiations carefully to avoid further diplomatic isolation and ensure the long-term viability of regional cooperation.[75]

At the same time, the unexpected fall of the Assad regime and the emergence of a new, potentially Turkey-aligned government in Syria could significantly reshape the energy dynamics of the Mashreq. Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has underscored Turkey’s role in Syria, stating in a CNN Türk interview, “We are against the idea of domination. We may have influence, they may take us as an example.”[76] He further declared, “Our story in Syria is just beginning,”[77] signalling Ankara’s continued engagement in shaping Syria’s future. A Turkey-aligned Syrian government could play a pivotal role in regional energy dynamics. In such a scenario, the Arab Gas Pipeline could gain renewed importance, linking Egypt’s resources through Jordan and Syria to all the Mashreq and Turkey, providing a more cost-effective land route for natural gas that bypasses Israel. Furthermore, a Turkey-friendly administration in Damascus might recognize Ankara’s EEZ claims in the Mediterranean reshaping regional maritime boundaries.

Ultimately, the development of the Eastern Mediterranean natural gas resources represents a test case for whether the region can transition from a zero-sum geopolitical environment to a more cooperative, connectivity-driven geography. While current obstacles remain formidable, the region’s energy potential offers an opportunity to rethink engagement strategies. A future-oriented approach, one that prioritizes inclusivity and long-term economic benefits over short-term political gains, could transform both the EMGF and EastMed from an unrealized ambition into a driver of regional stability and prosperity.

References

[1]Luigi Narbone, “Saving the Reconciliation Process in the Middle East and North Africa: Mission (Almost) Impossible?” Policy Paper 2023/01, Luiss Mediterranean Platform, 2023.

[2]Nadine Godehardt and Karoline Postel-Vinay, ‘Connectivity and Geopolitics: Beware the “New Wine in Old Bottles” Approach’, SWP Comment No. 35, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), 2020; Mark Leonard, Age of Unpeace: How Globalisation Sows the Seeds of Conflict, Transworld Publishers, 2021; Viktor Buzna et al., ‘Connectivity: Exploring the Concepts behind Today’s Geoeconomic Buzzword’, MKI Long brief, Magyar Külügyi Intézet (MKI), 2024.

[3]Luigi Narbone and Abdelkarim Skouri, ‘A Sea of Opportunities. The EU, China and the Mediterranean Connectivity’, Policy Paper 2024/08, Luiss Mediterranean Platform, 2024.

[4]Pascal Devaux, ‘Eastern Mediterranean: Natural Gas: A Regional Overview’, Eco Emerging, BNP Paribas Economic Research Portal, 2023.

[5]Julian Bowden and Elad Golan, ‘East Mediterranean Gas: A Triangle of Interdependencies’, Energy Insight No. 151, The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 2024.

[6]U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), ‘Eastern Mediterranean Energy’, Report, 2022.

[7]Roberta Gatti et al., MENA Economic Update (April 2024): Conflict and Debt in the Middle East and North Africa, World Bank, 2024.

[8]Bowden and Golan, ‘East Mediterranean Gas: A Triangle of Interdependencies’.

[9]Alexander Huurdeman, ‘An Emerging Natural Gas Hub in the Eastern Mediterranean’, World Bank, 2020.

[10]‘About Us – IGI Poseidon’, accessed 4 March 2025.

[11]Ibid.

[12]DNV, ‘DNV Confirms Feasibility, Maturity of EastMed Gas Pipeline’, Press release, 2022.

[13]Charles Ellinas, ‘East Med Gas: The Impact of Global Gas Markets and Prices’, IAI Commentaries 19 | 16, Istituto Affari Internazionali, 2019.

[14]Carole Nakhle, ‘Decline of Russian Gas Dominance in Europe’, Geopolitical Intelligence Services (GIS), 2025.

[15]Energypress, ‘New Effort for East Med Agreement at Athens Energy Summit’, News, August 6, 2018; EKathimerini.Com, ‘EastMed Pipeline Viability under Scrutiny’, News, March 13, 2021.

[16]Georgios Papadimitriou, “Greece Goes the Distance, Continuing to Win Investors’ Trust”, EY Greece, October 3, 2023.

[17]‘About Us – IGI Poseidon’, 2025.

[18]Nord Stream, “Nord Stream Transported 200 Billion Cubic Metres of Natural Gas to European Consumers”, Press release, November 30, 2017.

[19]‘The TurkStream Pipeline’, accessed March 4, 2025.

[20]DNV, ‘DNV Confirms Feasibility, Maturity of EastMed Gas Pipeline’, 2022.

[21]Edison, ‘EastMed-Poseidon Pipeline: A Direct Interconnection between Sources and Markets’, accessed March 4, 2025; ‘EastMed-Poseidon – IGI Poseidon’.

[22]USA EIA, ‘Eastern Mediterranean Energy’, 2022.

[23]Steven Scheer, ‘Israeli Gas Group in Talks on Pipelines to Turkey, Jordan, Egypt’, Reuters, August 6, 2013.

[24]Meliha Benli Altunışık, “Turkey’s Eastern Mediterranean Quagmire”, Middle East Institute, 18 February 2020.

[25]Turkey’s exploration activities in contested areas from a strictly legal point of view are not necessarily unlawful under international law see Konstantinos D. Magliveras and Gino J. Naldi, “The East Mediterranean Gas Forum: A Regional Institution Struggling in the Mire of Energy Insecurities”, International Organizations Law Review 20(2): 194–227, 2023.

[26]Cihat Yaycı, Maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) In Eastern Mediterranean, Deniz Basımevi Müdürlüğü (Maritime Publications Directorate), 2019; Simon Henderson, “Turkey’s Energy Confrontation with Cyprus”, The Washington Institute, July 24, 2019.

[27]Aurélien Denizeau, “Mavi Vatan, the “Blue Homeland” The Origins, Influences and Limits of an Ambitious Doctrine for Turkey”, Études de l’Ifri, Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri), April 29, 2021.

[28]Ioannis N Grigoriadis, “The Eastern Mediterranean as an Emerging Crisis Zone and Cyprus in a Volatile Regional Environment”, in M. Tanchum (ed.), Eastern Mediterranean in Uncharted Waters: Perspectives on Emerging Geopolitical Realities, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2021.

[29]Renee Maltezou, “Cyprus Accuses Turkey of Blocking Ship Again in Gas Exploration Standoff”, Reuters, February 23, 2018.

[30]Emre Karaca, “Türkiye’nin Sondaj Gemisi Yavuz, Karpaz Açıklarına Ulaştı”, Anadolu Ajansı , July 8, 2019.

[31]Muhammet İkbal Arslan, “Barbaros Hayreddin Paşa Sismik Araştırma Gemisi Doğu Akdeniz’deki Çalışmalarını Sürdürecek”, Anadolu Ajansı, July 30, 2020.

[32]Lorenzo Vita, L’Onda Turca, Il Risveglio Di Ankara Nel Mediterraneo, Historica / Giubilei Regnani, 2021.

[33]Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Republic of Türkiye), “Mavi Vatan Denizlerdeki Destanımızı”, August 2, 2024.

[34]‘EMGF’, accessed 4 March 2025.

[35]Magliveras and Naldi, “The East Mediterranean Gas Forum”, 2023.

[36]For instance, in November 2024, the EMGF participated and hosted different high-level events with EU and US officials, such as the Mediterranean Offshore Conference in Alexandria, on alliances for monetizing East Mediterranean gas, or the COP29.

[37]Magliveras and Naldi, “The East Mediterranean Gas Forum”, 2023.

[38]Mona Sukkarieh, “The East Mediterranean Gas Forum: Regional Cooperation Amid Conflicting Interests”, Briefing, Natural Resource Governance Institute, February 2021.

[39]Ibid.

[40]Esra Dilek, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy in The Eastern Mediterranean: Peacemaking in Cyprus at a Crossroads”, IPC-Mercator Analysis, Istanbul Policy Center (IPC), March 2023.

[41]Ibid.

[42]Tuvan Gumrukcu and Ezgi Erkoyun, “Erdogan Says Turkey Wants Deeper Ties with Egypt on Natural Gas, Nuclear Energy”, Reuters, September 4, 2024.

[43]Berat Albayrak, Burası Çok Önemli! – Enerjiden Ekonomiye Tam Bağımsız Türkiye, Turkuvaz Kitap, 2022.

[44]Francesca Landini, “EastMed Pipeline Project Still Viable, Edison CEO Says”, Reuters, 7 July 2023.

[45]Huurdeman, “An Emerging Natural Gas Hub in the Eastern Mediterranean”, 2020.

[46]Bowden and Golan, “East Mediterranean Gas: A Triangle of Interdependencies”, 2024.

[47]Alberto Rizzi and Arturo Varvelli, “Opening the Global Gateway: Why the EU Should Invest More in the Southern Neighbourhood”, ECFR, March 2023.

[48]European Commission, “New List of EU Energy Projects of Common and Mutual Interest”, accessed 4 March 2025; DEPA, “Eastern Mediterranean Interconnector Pipeline (EastMed)”, accessed 4 March 2025.

[49]Bradley Churchman, “Egypt’s Gas and LNG: Global Challenges and Global Ambitions”, RBAC Inc., 17 January 2024; BMI, “Declining Gas Production In Egypt Underlines Need For Further Discoveries”, July 18, 2023.

[50]One of these units set to operate in Ravenna, Italy.

[51]BMI, “Declining Gas Production In Egypt Underlines Need For Further Discoveries”, 2023.

[52]Mohamed Ezz Ezz, “Egypt, Cyprus Sign Gas Export Deals, Boosting Eastern Mediterranean Energy Cooperation”, Reuters, February 17, 2025.

[53]Noam Raydan Raydan, “The Gaza War’s Impact on Energy Security in the East Mediterranean”, Policy Analysis, The Washington Institute, November 1, 2023.

[54]Morten Valbjørn, André Bank, and May Darwich, “Forward to the Past? Regional Repercussions of the Gaza War”, Middle East Policy 31(3): 3-17, 2024.

[55]OilPrice.com, “Israel’s Gas Exports to Egypt Soar Despite Political Tensions”, March 20, 2024.

[56]Ayşegül Kahvecioğlu, “Karabağ’a Libya’ya Nasıl Girdiysek, Benzerini Yaparız”, Milliyet, July 29, 2024.

[57]Emile Badarin and Tobias Schumacher, “The Eastern Mediterranean Energy Bonanza: A Piece in the Regional and Global Geopolitical Puzzle, and the Role of the European Union”, Comparative Southeast European Studies 70(3): 414-38, 2022; Alissa De Carbonnel, “Examining U.S. Interests and Regional Cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean”, International Crisis Group, April 1, 2022.

[58]Joshua Krasna, ‘Politics, War and Eastern Mediterranean Gas’, Tel Aviv Notes 16(4), Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, March 24, 2022.

[59]Yücel Acer, “EastMed Projesinde Dönüm Noktasına Mı Geliniyor?”, Perspektif No. 326, Siyaset, Ekonomi ve Toplum Araştırmaları Vakfı (SETA), February 2022.

[60]European Council , “Where Does the EU’s Gas Come from?”, accessed March 4, 2025.

[61]Yair Lapid, “Statecraft in the Age of Connectivity: How Countries Can Work Together Even When They Disagree”, Foreign Affairs, December 15, 2022.

[62]Ibid.

[63]Sukkarieh, “The East Mediterranean Gas Forum”, 2021; Mona Sukkarieh, “Will the Rapprochement Unlock the Full Potential of the Eastern Mediterranean’s Natural Gas Wealth?”, Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), December, 23, 2024.

[64]Ioannis N. Grigoriadis and Deniz Çetin, “Energy Transition in the Eastern Mediterranean: Turning the East Mediterranean Gas Forum EMGF into a Regional Opportunity”, ELIAMEP, February 14, 2024.

[65]Daniel W. Drezner, Abraham L. Newman, and Henry Farrell, The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence (Brookings Institution Press, 2021).

[66]Mark Leonard, Age of Unpeace, 2021.

[67]Mark. Leonard, Connectivity Wars: Why Migration, Finance and Trade Are the Geo-Economic Battlegrounds of the Future (ECFR, 2016).

[68]John Power, “Houthi Red Sea Attacks Still Torment Global Trade, a Year after October 7”, Al Jazeera, October 5, 2024.

[69]Narbone and Skouri, “A Sea of Opportunities”, 2024.

[70]European Commission, “Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank: The Global Gateway”, December 1, 2021.

[71]Bowden and Golan, “East Mediterranean Gas: A Triangle of Interdependencies”, 2024. Ibid.

[72]Ibid.

[73]Yaycı, “Maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) In Eastern Mediterranean”, 2019.

[74]Grigoriadis and Çetin, “Energy Transition in the Eastern Mediterranean”, 2024.

[75]Bronwen Maddox, “Israel Needs a Strategy for Its Place in the Region That Is Not Just Attacks on Current Threats”, Chatham House, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, October 4, 2024.

[76]Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Republic of Türkiye), “Dışişleri Bakanı Sayın Hakan Fidan’ın CNN Türk’e Verdiği Mülakat”, January 7, 2025.

[77]NTV Haber, “Dışişleri Bakanı Hakan Fidan: Suriye’de Hikayemiz Yeni Başlıyor”, accessed March 4, 2025.

In Focus

Distribution of Powers in Libya’s Future Local Governance System

KHERIGI, Intissar

5 February 2026

Subnational Governance in Divided Societies: Learning from Yemen to Inform Libya’s Peace Process

MRAD, Mohamed Aziz

8 January 2026

Youth as Catalysts for Shaping Libya’s Future Pathways for Inclusion in National Dialogue and Vision -Making

SKOURI, Abdelkarim

2 December 2025