Hydrogen Valleys and Sustainable Development in Algeria: Pivoting from Hydrocarbons to an Inclusive Euro Mediterranean Hydrogen Economy

Executive Summary

Algeria stands at a critical juncture: abundant renewable resources, an extensive, though ageing, gas infrastructure, and geographic proximity to European and wider Mediterranean demand centres provide a once in a generation opportunity to reinvent its energy model. Building on the National Hydrogen Development Strategy, unveiled in March 2023, and recent international memoranda, this policy paper argues that a place -based Hydrogen Valley approach can anchor green hydrogen value chains inside Algeria, generating skilled employment, industrial diversification, and balanced Mediterranean cooperation. Moving well beyond pilot projects, we outline how a network of Hydrogen Valleys can interlink with the SoutH2 corridor, maritime ammonia shipping, and Maghreb electricity interconnectors to foster deeper regional integration. The analysis draws on a literature and open-source analysis, augmented with own research own analysis. Our findings indicate that, under an accelerated deployment scenario reaching 6 –10GW of electrolysis capacity by 2040, hydrogen could contribute 6 –9 % of Algeria’s GDP, generate up to 250,000 jobs, and reduce national CO₂ emissions by approximately 25–30 % compared to a business-as-usual hydrocarbon trajectory.

1. Introduction: Algeria’s Hydrogen Opportunity in a Changing Energy Landscape

The European energy transition, accelerated by the phaseout of Russian gas and the EU’sREPowerEU target of 20 Mt H ₂ imports by 2030, has fundamentally reshaped Euro -Mediterranean energy relations.[1] Algeria, historically Europe’s third -largest gas supplier, now faces two interlinked pressures: declining hydrocarbon rents as global demand peaks, and a domestic social contract reliant on subsidised fuels and public -sector employment.[2]

Green hydrogen offers a powerful dual promise: it can catalyse domestic socio -economic renewal while preserving Algeria’s strategic relevance as a long -term energy partner to Europe. To realise this potential, however, the country must move beyond enclave megaprojects towards territorially embedded Hydrogen Valleys that integrate production, infrastructure, end-use, and skills development.[3]

Algeria’s ambition to emerge as a ‘regional hydrogen leader’ rests on an exceptionally strong foundation of natural resources, infrastructure, and supportive policy. Its vast renewable energy endowment, a maturing regulatory framework, and legacy gas assets together provide the enabling conditions to launch a large-scale hydrogen economy. When combined, these factors create an opportunity to simultaneously decarbonise the domestic economy, diversify away from hydrocarbons, and reinforce Algeria’s integration into global clean-energy markets.

Among North African nations, Algeria possesses one of the richest yet most under-utilised renewable resource bases.[4] High-resolution solar mapping places its average direct normal irradiance (DNI) above 2,300 kWh m⁻² yr⁻¹, among the world’s highest, while its onshore wind potential exceeds 2,000 TWh yr⁻¹.[5] These complementary solar and wind assets can underpin hybrid configurations capable of achieving up to 6,500 full -load hours, enabling levelised costs of hydrogen (LCOH) between 5.3 and 3.4 €/kg by 2030.[6] This positions Algerian hydrogen as

markedly more competitive than potential suppliers such as Canada or Chile, estimated at 8.7 and 6.5 €/kg respectively.

Recognising this potential, Algeria adopted a National Hydrogen Development Strategy in May 2024. It sets clear milestones , 200 MW of pilot electrolysers by 2030, 6 GW by 2040 and 15 GW by 2050, while prioritising technology transfer and local job creation.[7] Key incentives include a 10-year corporate tax holiday for hydrogen projects, customs -duty exemptions on electrolyser imports, and a Hydrogen Development Fund capitalised at €1 billion to co -invest alongside private equity These measures signal a firm political commitment to pivot decisively toward a green -hydrogen economy.

Equally important, Algeria’s existing infrastructure provides a solid launchpad. The country operates more than 6,000 km of high-pressure gas pipelines, of which 4,200 km have been assessed as hydrogen-ready after minor retrofits (< 5 €/m).[8] Its ports, Arzew, Skikda and Béjaïa, already handle cryogenic LNG and ammonia, reducing capital expenditure for potential green -ammonia export terminals. Desalination capacity, currently 2.5 Mm³ d ⁻¹, can be scaled to meet

process-water demand at less than 2 L per kg H₂.[9]

Together, these factors paint an encouraging picture: Algeria is structurally equipped and strategically motivated to develop a competitive hydrogen economy. The indicative Hydrogen Valley impacts presented in this paper draw on open -source modelling to estimate potential GDP growth, employment generation, and trade gains arising from investment in a coordinated national hydrogen programme.[10] These insights underscore that, if pursued systematically, hydrogen could become the cornerstone of Algeria’s sustainable economic transformation.

2. The Hydrogen Valley Concept Applied to Alge

Establishing hydrogen valleys in Algeria is not just a question of technological feasibility or industrial clustering. It reflects a broader national vision to localise green value chains, ensure inclusive development, and decentralise the energy transitio n across different regions of the country. The Hydrogen Valley model, emphasising geographic concentration of hydrogen production, storage, distribution, and end-use, provides a replicable blueprint to maximise domestic benefits while preparing for international hydrogen trade. By aligning hydrogen production with regional strengths and needs, whether industrial, agricultural, or logistical, Algeria can ensure that hydrogen development contributes meaningfully to job creation, rural uplift, and balanced economic diversification.

The European Union defines a Hydrogen Valley as “a geographically concentrated ecosystem that clusters hydrogen production, storage, distribution and offtake within a defined region”.[11] The idea is to establish feasible production, transformation, transport and offtake routes within a certain geographic location by also utilizing any locally available assets such as area’s where hydrogen can be stored underground (empty gas fields, salt caverns), large scale off takers(industrial sites) or potential for mining and conversion. Once these have been identified , the development of a valley can be implemented througha four-phaseroadmap:(i) Early Design & Engagement, (ii) Feasibility & Road mapping, (iii) Final Design & Business Planning, (iv) Commercial Deployment can be utilized as used by Impact Hydrogen.

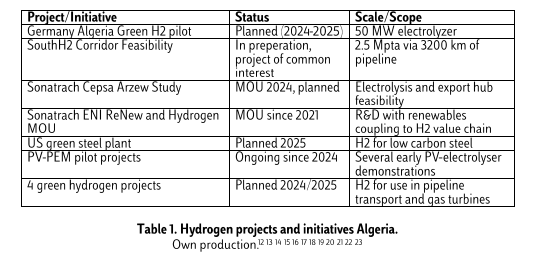

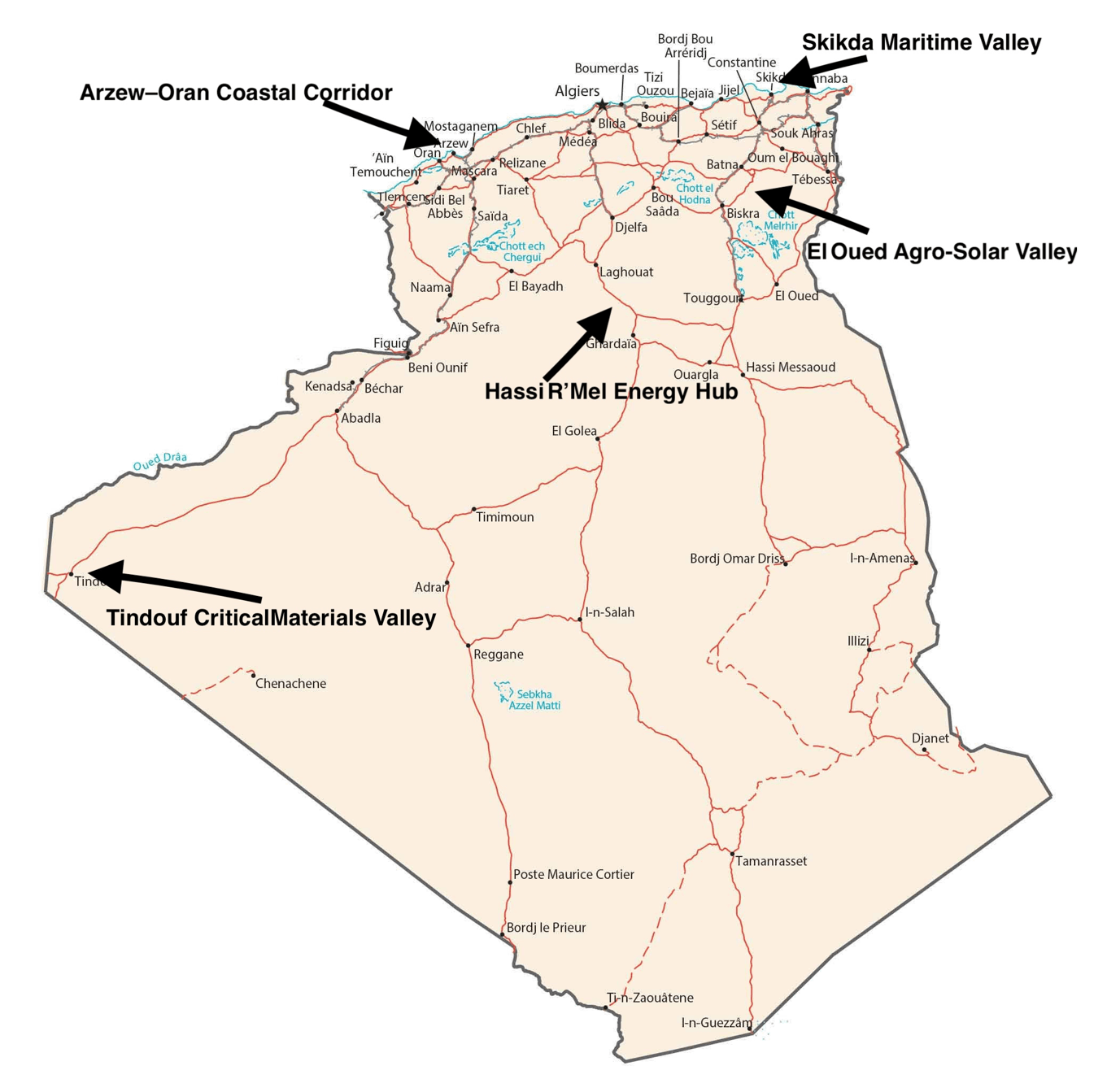

Based on our analysis of multiple sources we have established a list of projects and initiatives that involve hydrogen production, storage, transport and offtake. This serves as a basis for further analysis of attractive Hydrogen Valley set up.

Based on the above project list and Algeria’s geography and industrial fabric we suggest five distinct yet complementary valley pathways that could be explored further:

1. Hassi R’Mel Energy Hub– Repurposes depleted gas reservoirs for largescale subsurface hydrogen storage and provides the injection point for the SoutH2 export pipeline, while co locating a 1GW solar windelectrolyser park that can stabilise the national grid during peak demand months.

2. Arzew–Oran Coastal Corridor – Converts the nation’s largest ammonia and methanol complexes to green feedstock, upgrades quay infrastructure for liquid ammonia export, and pilots a 20% hydrogen blend in the Arzew refinery furnaces.

3. El Oued Agro-Solar Valley – Couples 300 MW PV electrolysis with green fertiliser production for date palmand olive cooperatives, providing an anchor industry in a region where youth unemployment exceeds 25%.

4. Skikda Maritime Valley – Focuses on e-methanol and ammonia bunkering fuel for Mediterranean shipping, taking advantage of existing cryogenic storage tanks and specialist workforce at the port of Skikda.

5. Tindouf CriticalMaterials Valley – Co-locates rareearth concentrate processing with hydrogen baseddirectreduction iron (HDRI), enabling downstream clean steelexports to neighbouring Morocco and European markets.

These valley concepts fully utilize the existing infrastructure and potential offtakes . Enabling Algeria to capitalize efficiently on a pivot towards a Hydrogen economy. Furthermore, embedding these valleys within existing provincial development plans (Plans Directeurs d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme, PDAU) ensures that land use, water rights and community benefit sharing are codified early, reducing later permitting friction.

3. Estimated Impacts of Hydrogen Valley Development in Algeria

While Algeria has yet to undergo detailed country -specific macroeconomic modelling for hydrogen deployment using tools such as the GTAP-Africa v11 CGE framework, robust estimates can be developed by drawing on recent open -access literature.[24] Using a recursive-dynamic CGE model calibrated to GTAP v11, modelled the macroeconomic effects of renewable energy investment across sub-Saharan Africa. Their findings suggest that sustained investment in solar and wind

infrastructure equivalent to 0.5% of GDP annually yields average GDP growth benefits of +0.15 to +0.40 percentage points per year over a ten -year horizon, depending on the financing mix. GDP gains were notably higher in scenarios where international climate finance provided half of the capital expenditure, owing to reduced domestic crowding -out effects and stronger stimulus from imported capital goods. Although the geographical and climatological aspects of Algeria and

Northern Africa are different from sub-Saharan Africa, this publication and model are useful to utilize nonetheless because it provides a close reference to the potential impact of deployment of renewables at scale.

Applying these growth elasticities to Algeria, we constructed three hydrogen deployment pathways: a Conservative (2 GW), an Accelerated (6 GW), and a Hydrogen Leap (10 GW) scenario, with estimated investments ranging from US $6 billion to US $32 billion over the 2025–2035 period. Based on Algeria’s renewable resources, electrolyser efficiency and assumed capacity factors, these scenarios could yield between 0.6 and 3.0 million tonnes of hydrogen annually by 2035. When valued at €2.00 per kg (IEA Central Cost Scenario), the net trade benefit, after subtracting domestic production and logistics costs , i estimated between US $1.3 billion and US $6.5 billion annually.

For employment, we drew on IRENA’s job multipliers, which estimate 5 –7 job-years per MW in the construction phase and approximately 0.3 –0.5 operations and maintenance (O&M) jobs per MW thereafter. Additional employment was assumed in downstream sectors suc h as green ammonia, fertilizers, and hydrogen-based fuels. When including indirect and induced employment through economic multipliers (≈2.5×), the total number of new jobs created by 2035 is estimated to be

between 70,000 in the Conservative scenario and up to 260,000 under the Leap pathway.

These indicative figures suggest that, even under modest deployment, Algeria’s hydrogen programme could modestly lift GDP growth (by 0.15 –0.40 pp annually), substantially improve the country’s trade balance (by 2–11% of current goods exports), and create tens to hundreds of thousands of jobs. The financing structure is key: international co-financing or concessional funding significantly amplifies positive macroeconomic outcomes by reducing domestic investment displacement.

Furthermore, from an environmental perspective, green hydrogen replacing grey hydrogen in refinery hydrogen, ammonia production, steel production and as fuel exports can cut emission 25–35 Mt CO₂-eq annually[25],[26]). That would reduce Algeria’s national emissions by around 20–30%, based on current national emissions (110 –5 Mt CO₂-eq/yr).

The Hydrogen Valley rollout advances nine UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG8 (Decent Work), SDG9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG13 (Climate Action). Beyond these ‘global’ goals, alignment with the African Union’s Agenda2063 and the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) would also preserve market access for Algerian exports.

These macroeconomic projections , environmental benefits and SDG goals, further strengthen the rationale for embedding hydrogen development within Algeria’s broader economic diversification strategy. Beyond climate mitigation and industrial innovation, Hydrogen Valleys offer a platform for inclusive development and fiscal resilience, especially in the context of long -term hydrocarbon revenue decline.

4. Deepening Mediterranean Cooperation and Regional Integration

The establishment of a green hydrogen economy in Algeria offers an unprecedented opportunity to redefine the country’s role in the Euro -Mediterranean region, not merely as an energy exporter, but as a collaborative partner in the shared pursuit of climate resilience and sustainable development. Through the development of infrastructure corridors, maritime trade routes, electricity interconnectors, and innovation networks, Algeria is strategically positioning itself as a central node in the emerging Mediterranean hydrogen ecosystem.

These opportunities go beyond technical integration. They support a broader vision of regional interdependence built on clean energy flows, shared research and development initiatives, and balanced trade arrangements. The emerging SoutH2 and GALSI 2.0 pipeline projects anchor Algeria to European hydrogen demand centres, while the proposed MedHyEast route and cross -border electricity links with Spain and Morocco establish Algeria as a key connector between Africa and Europe. Such connections will not only en able hydrogen exports but can also improve Algeria’s domestic energy resilience and industrial development.

Similarly, the modernisation of ports for green ammonia shipping and participation in Mediterranean bunkering markets underscore Algeria’s potential to lead in maritime energy transitions. Trade facilitation tools , such as green cumulation of origin clauses and concessional finance mechanisms, can further integrate Algerian products into EU value chains. Meanwhile, collaboration in research, innovation, and training, such as through the proposed H₂ Med-Lab, enables the co-creation of intellectual capital and strengthens Algeria ’s human development base. In sum, this new energy chapter is not just about export volumes or infrastructure, but about repositioning Algeria as a cooperative, innovative and resilient partner at the heart of a greener Mediterranean space.

To illustrate the existing and upcoming opportunities further in March 2025, Algeria, Tunisia, Italy, Austria and Germany signed a Declaration of Intent to develop the 3,300 km SoutH ₂ Corridor, designed to transport up to 4 Mt H₂ per year, equivalent to 40 percent of the EU’s import target , by repurposing around 65 percent of existing gas pipelines (South2Corridor 2025). Feasibility studies indicate a levelised transport cost of about 0.15 €/kg along the Hassi R’Mel –Bavaria route.

In parallel, a complementary MedHyEast spur, now under scoping, would link Skikda to Greece via Libya, offering Algeria an important diversification hedge against dependence on a single export route27. Reviving the GALSI route to Sardinia and mainland Italy (GALSI Phase 2) could further unlock markets for island decarbonisation and inter -seasonal hydrogen storage.

Beyond pipelines, maritime transport will also play a strategic role. Green ammonia shipping from Arzew and Skikda to major European bunkering hubs such as Rotterdam and Trieste could build on Algeria’s existing cryogenic infrastructure. DNV[28] estimates ammonia bunker fuel demand to reach 245Mt per year by 2050, underscoring the scale of this opportunity. A 30,000 -tonne storage tank and loading arm at Arzew would cost roughly €120 million, less than 3 percent of total Hydrogen Valley capital expenditure , making this a cost-effective export vector.

Electricity connectivity and grid integration are equally important enablers. Algeria is negotiating a 3 GW HVDC link with Spain (MedCable) and exploring integration within the Maghreb –Europe Electricity Market (MEEM). By coupling curtailed solar and wind power with flexible electrolysers, hydrogen plants could raise their load factors by 8–12 percent, improving both operational efficiency and overall bankability.[29]

On the research and innovation front, Algeria is well placed to co -lead H₂MedLab, a proposed Horizon Europe partnership involving Italian, Tunisian and Egyptian universities. The programme would target PEM catalyst substitution using domestic phosphates and operate under a Technology Access Pool inspired by the COVAX model to en sure equitable intellectual -property sharing.[30]

Trade and investment frameworks are also evolving to support this transformation. Introducing a “green Cumulation of Origin” clause into the EU–Algeria Association Agreement would allow Algerian hydrogen derivatives to count toward EU domestic -content requirements, reducing tariff barriers.[31] Financially, the European Investment Bank has earmarked €1.2 billion in concessional loans under its Southern Neighbourhood Facility, while the African Development Bank’s Desert –

to-Power initiative can co-finance grid and transmission infrastructure.

Ensuring a just and inclusive transition will be essential. Lessons from the Ruhr and Asturias regions[32] highlight the value of early and structured social dialogue. A proposed Algerian Hydrogen Social Compact could formalise local employment quotas, community equity stakes of up to 10 percent, and gender-sensitive procurement practices, embedding social res ponsibility within the emerging hydrogen economy.

Finally, industrial diversification and circularity are critical for long -term resilience. Expanding electrolyser deployment will increase demand for iridium, nickel and yttrium, materials where Algeria’s phosphate and nascent rare -earth reserves offer pot ential for vertical integration. A pilot solvent-extraction facility in Tindouf could supply around 600 kg of iridium equivalent annually for domestic PEM stacks by 2030[33]. To close the loop, a circular -economy framework aligned with the EU Battery Regulation should require 90 percent catalyst recovery at end of life , an initiative capable of generating a domestic recycling industry worth around €150 million per year by 2040, while enhancing resource security and environmental performance.

5. Risk Landscape and Mitigation

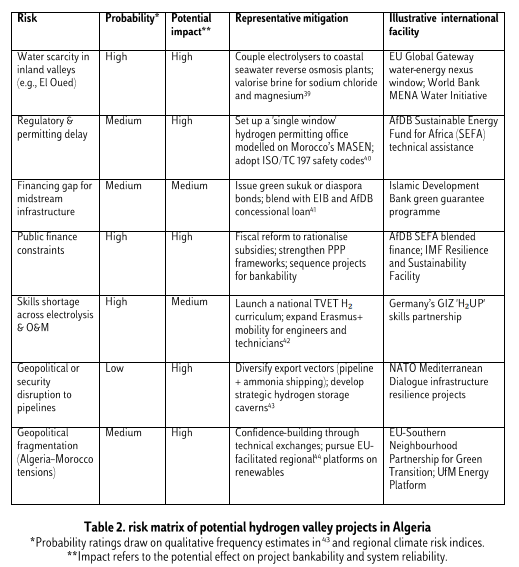

Establishing a hydrogen economy through favourable hydrogen valley concepts has several key risks that need to be mitigated. Literature assessments from the IEA[34], IRENA[35] and the World Bank[36] highlight five clusters of risk that are most salient for Algeria’s hydrogen rollout: (i) water availability in arid zones, (ii) regulatory and permitting complexity, (iii) access to finance, (iv) skills gaps in the emerging hydrogen labour market, and (v ) geopolitical or security interruptions along export routes. Table 2 consolidates these risks, indicates their qualitative probability and impact, and lists mitigation measures together with international facilities that Algeria can tap into.

One additional geopolitical dimension concerns the frozen relationship between Algeria and Morocco. Despite both countries’ strong renewable endowments and geographical complementarity, joint ventures such as a potential Tindouf Hydrogen Valley remain politically unfeasible at present. The 2025 Diplomeds –FES[37] report estimates that Algeria alone has spent more than USD 2 billion on border fortifications between 2013 and 2020, illustrating the opportunity costs of non-cooperation. While the current rupture prevents any meaningful cross -border hydrogen corridor, the novelty of hydrogen as a transformative energy vector could eventually serve as an entry point for re-engagement, should diplomatic conditions improve. In that sense, hydrogen cooperation is both a risk , through lost synergies, and a latent opportunity for long-term regional stability.

A second critical risk relates to financing capacity. Algeria’s macro -fiscal space has tightened in recent years due to fluctuating hydrocarbon revenues, persistent subsidy burdens, and limited diversification. The World Bank36 notes that Algeria’s public investment program has been repeatedly curtailed under budgetary pressures andhighlights structural weaknesses in mobilizing private capital for energy infrastructure. Moreover, debt[38] sustainability analyses classify Algeria as

facing elevated fiscal risks from volatile oil and gas export earnings. These constraints heighten the difficulty of financing midstream hydrogen infrastructure such as pipelines, storage, and conversion facilities, which require multi-billion-dollar outlays with long payback horizons. Mitigation options exist, green sukuk issuance, diaspora bonds, and concessional facilities from partners such as the AfDB’s SEFA or the Islamic Development Bank , but their successful deployment hinges on regulatory reforms and credible project pipelines. For now, financing risk

remains a binding constraint that could delay large -scale rollout even if technical and resource conditions are met.

Addressing these risks early is essential not only for individual project viability but also for sustaining public trust and policy coherence. For example, desalination coupled electrolysis has been successfully demonstrated at industrial scale in the Middle East, bringing specific energy consumption down to 3kWh m⁻³, evidence that Algeria can draw upon. Likewise, Morocco’s one stoprenewable permitting agency reduced average approval times from 36 to 9 months, offering a replicable governance blueprint. As mentioned,leveraging multilateral funds such as AfDB

SEFA, and pairing them with Islamic finance instruments like green sukuk, Algeria canlso close its infrastructure financing gap without overburdening public debt. Finally, embedding hydrogen skills modules in existing TVET centres will be decisive for translating capital investment into lasting employment benefit.

6. Implementation Outlook and Key Milestones

Achieving Algeria’s hydrogen ambitions requires a coordinated, phased strategy that aligns local Hydrogen Valley development with national policy goals and Euro -Mediterranean cooperation frameworks. While drawing inspiration from earlier proposals, this paper integrates new evidence and open-source insights to present a refined implementation roadmap. The focus is on aligning hydrogen rollout with economic diversification, infrastructure readiness, skills development, and

international market access.

In the short-term Algeria should focus its action to achieve the following objectives:

• Reach financial close on at least two anchor projects , e.g. Arzew Coastal Valley and Hassi R’Mel Energy Hub, with a minimum of 1 GW combined electrolyser capacity.

• Publish a revised Hydrogen Investment Guide clarifying fiscal incentives, permitting procedures, and off -take support mechanisms.

Launch a national Green Skills Observatory hosted by a local institution (e.g., the University of Boumerdès) to monitor labour demand and inform vocational curricula.

Key priorities for the medium term include:

• Establishing a Hydrogen Valley Coordination Office to align infrastructure, permitting, and investor facilitation across ministries and wilayas.

• Completing FEED studies for export infrastructure, including the SoutH2 pipeline (Hassi R’Mel to Bavaria) and green ammonia terminals at Skikda and Arzew.

• Piloting local content quotas and gender -equal procurement policies in hydrogen -related public-private partnerships.

• Hosting the first “Algeria–EU Hydrogen Investment Forum” to mobilize concessional and blended finance with European institutions.

By 2030, Algeria should target:

• Operationalisation of at least 4 –5 geographically distributed Hydrogen Valleys integrated with industrial clusters (e.g. fertilisers, green steel, shipping).

• Commissioning of maritime export terminals and ammonia bunkering capacity at Skikda and Arzew.

• Grid integration of flexible electrolysers through HVDC interconnection with Spain and expanded links to Morocco(when political tensions allow)and Tunisia.

• Release of the first national Just Transition Progress Report, documenting employment, regional development, and community benefit outcomes.

Collectively, these milestones would position Algeria as a leading green hydrogen exporter and regional clean-tech hub, while ensuring that domestic value creation and social inclusion remain at the heart of its hydrogen economy.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Algeria stands at a pivotal moment: endowed with exceptional renewable energy resources and a legacy energy infrastructure, it has the potential to leapfrog into a leading position in the global hydrogen economy. This policy paper demonstrates that a Hydro gen Valley approach, rooted in regional integration, local value creation, and sustainability, offers a practical and scalable pathway for this transformation.

Based on open-source modelling and scenario analysis of cases showing similarity to the Algerian context, hydrogen could contribute up to 14% of Algeria’s GDP by 2040 under an accelerated development trajectory. In employment terms, hydrogen -related activities, spanning electrolyser deployment, green ammonia production, and associated industries , could generate up to 310,000 new jobs, significantly outpacing those created under a hydrocarbon-dependent baseline. Furthermore, national CO₂ emissions could decline by 26–37%, depending on the scale and speed of deployment.

To translate this potential into reality, the following policy measures are recommended:

• Fast-track two anchor Hydrogen Valleys , Hassi R’Mel and Arzew, by 2027, with at least 2 GW of electrolyser capacitycommissioned, front -end engineering completed, and export infrastructure (pipeline or port) under development.

• Establish institutional coordinationthrough a dedicated Hydrogen Valley Coordination Office to oversee permitting, incentives, infrastructure planning, and regional development alignment.

• Expand the Hydrogen Development Fund to at least €3 billion by 2030, using hydrocarbon windfall revenues, green bonds, diaspora investment vehicles, and Islamic finance instruments such as sukuk.

• Introduce a Just Transition Taxonomy , modelled after the EU’s social and environmental finance standards, to prioritise inclusive projects in underdeveloped regions and ensure fair labour practices, especially for women and youth.

• Build international partnerships: Launch an Algeria–EU Hydrogen and Critical Materials Partnership focused on harmonising trade rules, investment pipelines, R&D cooperation, and supply chain resilience.

• Operationalise H₂Med-Lab, a regional R&D platform linking Algerian universities with Mediterranean peers to build innovation capacity in green hydrogen, catalyst development, and critical raw materials processing.

• Integrate energy and trade infrastructure: Coordinate hydrogen deployment with electricity interconnectors (e.g., MedCable), the SoutH2 pipeline, and ammonia maritime routes to increase system flexibility, regional market access, and export competitiveness.

In conclusion, the development of hydrogen valleys in Algeria is not simply an energy project. It is a national development opportunity that can diversify the economy, create thousands of high-quality jobs, and place the country at the heart of a cooperative and clean Mediterranean future.

8. Annex: Methodology

This study relies exclusively on open-source data, peer-eviewed literature, and publicly available modelling tools, complemented by our own spatial clustering analysis of potential Hydrogen Valley sites in Algeria. The analytical workflow proceeds in three layers:

1. Geo-Spatial Cluster Identification

Data sources: Global Solar Atlas v3 (DNI, GHI), Global Wind Atlas v3, OpenStreetMap port and pipeline layers, and the World Resources Institute Aqueduct 4.0 water -stress index. Approach: Using QGIS, we overlaid renewable-resource raster layers with existing gas infrastructure, industrial zones, and water -availability indices to delineate five high-synergy “valley” polygons (Hassi R’Mel, Arzew–Oran, El Oued, Skikda, Tindouf). Each polygon represents a 50–150 km radius catchment around anchor assets such as ports, gas processing hubs, or major solar fields.

2. Techno-Economic Cost Modelling

Data sources: IEA Hydrogen Projected Costs Model (HPCM v3.2, freely downloadable), IRENA Renewable Cost Database (2023 release), and BloombergNEF electrolyser benchmarks (public summary tables).Approach: Levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) trajectories (2025–2040) were calculated for each valley by combining localised capacity-factor data with open-source CAPEX/OPEX assumptions. Sensitivities were run for ±10 % electrolyser CAPEX, ±15 % renewable CAPEX, and a ±5 % discount-rate band.

3. Macro-economic Scenario Analysis

Data sources: IMF Staff Climate Note by Cai et al. (2024), World Bank Development Indicators (2023), IRENA job multiplier datasets. Approach: Elasticities derived from Cai et al.’s GTAP-based modelling were applied to three investment pathways, Conservative, Accelerated, and Leap, representing rising shares of GDP invested in hydrogen over the 2025 –2040 period. Employment projections were triangulated using IRENA’s renewable-job coefficients for construction and O&M phase

References

[1] European Commission, “REPowerEU Plan,”COM/2022/230 Final, 2022.

[2] Sara Brzuszkiewicz, “The Social Contract in the MENA Region and the Energy Sector Reforms,” ESP: Energy Scenarios and Policy253217, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei , 2017.

[3] IRENA,Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: Hydrogen , 2022.

[4] Ahmed Bouraiou et al.,“Status of renewable energy potential and utilization in Algeria, ” Journal of Cleaner Production246, February 10, 2020.

[5] IRENA,Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen Factor, 2023.

[6] Karl Seeger, “Techno-economic analysis of hydrogen and green fuels supply scenarios assessing three import routes: Canada, Chile, and Algeria to Germany,”International Journal of Hydrogen Energy , 116, 558–576, 2025.

[7] SGS Inspire,“Algeria: National Strategy for Hydrogen Development Publis hed,”Policy Alert14/2024, 2024.

[8] Sonatrach, “Technical Feasibility Study on Hydrogen Readinessof Gas Pipelines,” 2024.

[9] Amina Chahtou, Brahim Taoussi, “Techno-economic of solar-powered desalination for green hydrogen production: Insights from Algeria with global implications, ” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy ,Volume 121, 2025.

[10] Kaihao Cai et al.,“Harnessing Renewables in Sub-Saharan Africa: Barriers, Reforms, and Economic Prospects ,”IMF Staff Climate Note 2024/005, IMF, 2024.

[11] M. Bampaou, K.D. Panopoulos, “An overview of hydrogen valleys: Current status, challenges and their role in increased renewable energy penetration, ”Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews ,Volume 207,2025.

[12] European Hydrogen Backbone, “SoutH2 Corridor: Connecting North Africa to Central Europe ,” 2024.

[13] Snam, “Hydrogen Corridor Project Launch,”Press Release, 2024.

[14] European Commission- DG Energy, “Projects of Common Interest – 6th Union List under TEN-E Regulation,”2024.

[15] Cepsa, “Cepsa and Sonatrach sign MoU on green hydrogen at Arzew, ”Press Release, October 2024.

[16] Eni, “Eni and Sonatrach sign agreement on renewable energy and hydrogen development in Algeria, ” Press Release.

[17] LeadIT & BloombergNEF,Green Steel Tracker, Algeria project entries (2024). Accessible here: https://www.greensteeltracker.org/

[18] HYDROSOL II Project Consortium , CORDIS Project ID 502705 , 2007. Accessible here: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/20030/reporting/

[19] Amina Chahtou, Brahim Taoussi, “Techno-economic of solar-powered desalination for green hydrogen production,” 2025.

[20] Centre de Développement des Énergies Renouvelables (CDER), “PV–PEM Hydrogen Demonstration in Algerian Sahara Conditions,”2015.

[21] Renewables Now, “Algeria to launch four green hydrogen pilots by end -2024,” October 3, 2023.

[22] OECD,OECD Economic Outlook2023- Issue 2, 2023.

[23] IEA,Global Hydrogen Review 2023 , 2023.

[24] KaihaoCai et al., “Harnessing Renewables in Sub -Saharan Africa,”2024.

[25] IEA, Global Hydrogen Review 2023.

[26] IRENA,Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation, 2023.

[27] Dii Desert Energy,MENA Energy Outlook 2025 –Renewables, Hydrogen and Energy Storage Insights 2030 , 2025.

[28] DNV, Decarbonizing Shipping with Ammonia Fuel, 2023.

[29] Med-TSO – Mediterranean Transmission System Operators , “Masterplan of Mediterranean Interconnections, 2030 Reference Scenarios,”2023.

[30] Gabriele Marchionna, “Green Hydrogen and New Trans -Mediterranean Dynamics” Policy Paper, Luiss Mediterranean Platform.

[31] European Commission – DG Trade, “Cumulation, Rules of Origin, Concept Background Explainer.”

[32] Wuppertal Institute, “Just Transition Toolboxfor Coal Regions,” 2022.

[33] Leon Stille, “Securing critical materials across the Mediterranean, ”Policy Brief, Luiss LEAP, 2024.

[34] IEA, Global Hydrogen Review 2023 , 2023.

[35] IRENA, Geopolitics of theEnergy Transformation, 2023.

[36] World Bank, “ World Development Indicators: Algeria, ” Databank, 2023.

[37] Diplomeds & Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Competence Center MENA Peace & Security , “Morocco and Algeria Beyond the Divide: From Costs of Non-Engagement to Pathways for Cooperation,” January 2025.

[38] IMF, “Algeria: 2023 Article IV Consultation and Selected Issues, ” IMF Country Report No. 23/120 , IMF, 2023.

[39] Shanu Mishraet al., “Breaking down the barrier: The progress and promise of seawater splitting, ” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy106, 334-352,2025.

[40] World Bank, “World Development Indicators: Algeria ,” 2023.

[41] African Development Bank, “Sustainable Bond Program,” accessed September 5, 2025.

[42] IRENA, Geopolitics of t he Energy Transfor mation, 2023.

[43] IEA. Hydrogen production & infrastructure projects database, living database.

[44] European Commission,“Economic and Investment Plan for the Southern Neigbours,” Factsheet, March 2024.

In Focus

Youth as Catalysts for Shaping Libya’s Future Pathways for Inclusion in National Dialogue and Vision -Making

SKOURI, Abdelkarim

2 December 2025

Hydrogen Valleys and Sustainable Development in Algeria: Pivoting from Hydrocarbons to an Inclusive Euro Mediterranean Hydrogen Economy

STILLE, Leon

21 November 2025

The Digital Scramble for Africa:Why Cyber Diplomacy Matters

NFORBA, Sabina

9 October 2025