Levels of Government and Administrative Boundaries in Libya’s Future Local Governance System

1. Introduction

Since the early formation of states, the drawing of internal borders has been a key tool for asserting control over territory and populations. Internal administrative boundaries carry considerable political, economic, and social significance. They grant symbolic recognition and material advantages to specific regions and their residents, while shaping collective identities, local

belonging, and everyday practices such as mobility and socio-economic exchanges.

This paper examines the issue of levels of government in Libya’s future local governance system, with particular attention to the issue of administrative boundaries. Should a peace agreement include local governance reforms, Libya will inevitably face the challenge of redefining the boundaries and powers of subnational units, whether provinces/regions, or municipalities.

In the Libyan context, this is a contentious issue shaped by strong local identities, inter-tribal rivalries, and the presence of competing armed groups within the same areas. These dynamics have created de facto borders that often differ from official ones. Any revision of the administrative map must therefore be grounded in a fair and inclusive process, one that takes local

realities into account and involves a broad range of actors. Top-down attempts to impose new boundaries without such engagement risk reinforcing existing divisions or triggering new disputes.

This paper is based on interviews with a diverse group of Libyan stakeholders during July to September 2023 and an in-person

workshop in February 2024, including local governance experts, academics, and representatives of political and social constituencies. It also builds on existing research into Libya’s administrative history and the current governance landscape.

The paper is the second in a series of papers on the future of local governance in Libya, each focusing on a different dimension of the issue. By discussing and clarifying key concepts, capturing a range of perspectives, and drawing lessons from other countries’ experiences, the series aims to support informed dialogue among Libyans and the development of a governance model that meets the needs and aspirations of the Libyan people.

1.Historical Background of Administrative Divisions in Libya

As noted in the first paper1 of this series, Libya’s administrative divisions have undergone several changes since the start of Ottoman rule (1551–1911), which divided the territory. The 1864 Law on Provincial Administration reorganized Libyan territory into five sanjaks: Tripoli, Al-Khums, Jabal al-Gharbi, Fezzan, and Benghazi. These were further subdivided into qadha’at (districts), some of which were in turn divided into nawahi (subdistricts). This structure reflected zones of military control and the demands of tax collection, alongside weak central authority over interior regions, particularly in the south, where Fezzan was administered with relative flexibility due to its remoteness from the center and the strength of local influence. In 1871, municipalities were introduced as administrative units, each headed by a mayor and supported by an advisory municipal council. This represented the first formal attempt to implement local governance in urban areas, although municipalities remained largely symbolic and subject to the authority of the wali (provincial governor).

Following the start of Italian colonization in 1911, Libya’s administrative divisions were once again reorganized. After independence in 1951, a federal monarchy was established under King Idris, composed of three autonomous regions: Cyrenaica (Barqa), Tripolitania, and Fezzan. The federal system emerged as a compromise between regions that had developed semi-independent political and administrative identities, in part due to the isolation imposed by Italian colonial rule. Each region had its own government and local legislative council. However, the federal arrangement was short-lived and faced significant political, administrative, and economic challenges, particularly due to disparities in resources and infrastructure. These challenges led to increasing demands for unification.

On 26 April 1963, the constitution was amended to abolish the federal system and restructure the country into ten provinces: Al-Bayda, Al-Khums, Ubari, Al-Zawiya, Benghazi, Derna, Gharyan, Misrata, Sabha, and Tripoli[2]. These were further subdivided into districts and sub-districts, each headed by officials appointed by the central government. Decree No. 13 of 1963 defined the governor as the representative of the national government within the province, responsible for overseeing the implementation of national policies and regulations. While this role reflected strong central control over policy setting and implementation, it also established local executive capacity that can be built upon in future.

When Muammar Gaddafi came to power in 1969 and proclaimed the Libyan Arab Republic, the structure of local governance was reshaped in line with the doctrine of “popular administration.” Although the number of provinces remained unchanged, the organization of administrative units was unstable. Municipalities were dissolved and replaced by shaabiyat (people’s districts). The regime’s highly centralized approach deepened marginalization in certain areas and progressively weakened the authority of both provinces and municipalities. This legacy contributed to the calls for decentralization that emerged after 2011.

In 2017, Libya’s draft constitution introduced a proposed new framework for administrative boundaries under Article 144, which states: “The state shall be divided into governorates and municipalities, based on national security considerations and balanced criteria including population, area, geographic coherence, economic and historical factors, in a manner that promotes social justice, social harmony, and development, while ensuring efficiency and effectiveness. Additional administrative units may be established if required by the public interest, as defined by law.”

2. Levels of Government

According to Law 59 of 2012 on Local Administration, Libya’s subnational levels of government currently comprise governorates, municipalities, and sub-municipal entities. However, one of the most pressing challenges for

local governance today is the absence of the second tier – governorates – in reality. This missing layer between municipalities and the central government has created a significant gap, particularly in sectors requiring coordination across municipalities, such as regional transport, groundwater management, and local security. The absence of this intermediary tier has placed an excessive burden on the central government, while also limiting the ability of municipalities to function effectively. Reinstating the governorate level is therefore a practical necessity. Nevertheless, repeated attempts by the Presidential Council and the Government of National Unity to reintroduce governorates or regional units have stalled, largely due to disagreements over their boundaries[3].

Interviews with Libyan stakeholders on the country’s future local governance system have revealed broad consensus on the importance of maintaining a three-tier structure: (1) the national or central government, (2) regions, governorates, or provinces, and (3) municipalities. This fundamental agreement represents a point of strength in the Libyan context. However, it is essential that these tiers are not merely formal or symbolic; each must be

endowed with clearly defined roles, powers, and mechanisms for mutual oversight and accountability. Experiences from other countries in the region, such as Tunisia and Morocco, demonstrate that ambiguity in the relationships between different levels of government can undermine decentralization and hinder effective service delivery.

Some advocates of advanced decentralization have suggested a four-tier model: central government, “economic regions” composed of multiple governorates, governorates, and municipalities. Each economic region would be overseen by a Planning and Development Council made up of governors and municipal mayors from the region, with decisions requiring a two-thirds majority to ensure fair representation of smaller or less populated areas. This model could promote horizontal coordination and reduce developmental disparities, particularly in light of the stark imbalance in resources between Libya’s regions. However, the viability of such a system would depend on the presence of effective regional planning institutions, as well as giving economic regions sufficient financial and administrative autonomy and coordinating powers, all of which would require substantial legal and structural reform.

The main disagreement regarding governance levels in Libya concerns whether to establish regions or provinces with broad powers. Some argue in favor of a federal system, with directly elected legislative and executive

institutions at the regional level that share authority and resources with the central government. Others support a model of “advanced decentralization,” which would grant greater powers and resources to local authorities while maintaining a single national legislature and executive. At its core, this disagreement reflects deeper political and historical tensions over how power is distributed across regions. Proponents of federalism often refer to Libya’s pre-1963 federal experience; however, it is worth recalling that this arrangement emerged from a fragile balance among three regions that lacked a unified national foundation. Opponents of federalism fear that it could lead to state fragmentation. They emphasize the need for clear mechanisms of coordination between different levels of government, alongside broader efforts to strengthen national unity and reduce the risk of secession[4].

3. Proposals for New Administrative Divisions

Any future local governance system in Libya will encounter challenges in defining administrative boundaries between governorates, regions, or municipalities, due to complex social and political dynamics. In some cases,

local communities or tribes reject being grouped within the same governorate out of fear of domination by other groups, a fear often rooted in a long history of marginalization and a lack of trust in legal guarantees for equitable power-sharing within administrative units. These concerns are among the reasons why the Government of National Unity postponed the creation of governorates. In a speech to the House of Representatives in July 2021, Prime Minister Abdelhamid Dabaiba stated that “among the obstacles to implementing the provincial system currently are disagreements regarding some cities’ refusal to join forces with each other, which could even lead to threats of war[5].”

In parallel, a range of proposals for administrative boundaries have emerged from political parties, civil society organizations, and experts. The main proposals raised by research participants are summarized below.

3.1. Creating 12 Provinces or Regions

Some propose creating 12 provinces or regions in a way that promotes balance and reduces disparities between rich and poor areas of Libya. Another suggestion is to establish economic regions, with each region grouping two governorates – except for Tripoli and Benghazi, which would make up separate economic regions given their size. This proposal helps avoid geographic concentration and promotes integrated regional planning. However, its success depends on granting the governorate and regional levels sufficient legal powers and financial resources.

3.2. Creating 3 Regions

Some propose creating three regions – Fezzan, Cyrenaica (Barqa), and Tripoli – based on their status as historical units that reflect the diversity of Libyan society. While this proposal carries strong symbolic significance, it also entails several risks: (1) concerns that one or more regions might seek secession, reviving the geographic divisions that the previous federal system

failed to resolve; (2) the risk that a major city or dominant tribe within a region could monopolize power and marginalize smaller regions or tribes in the same region.

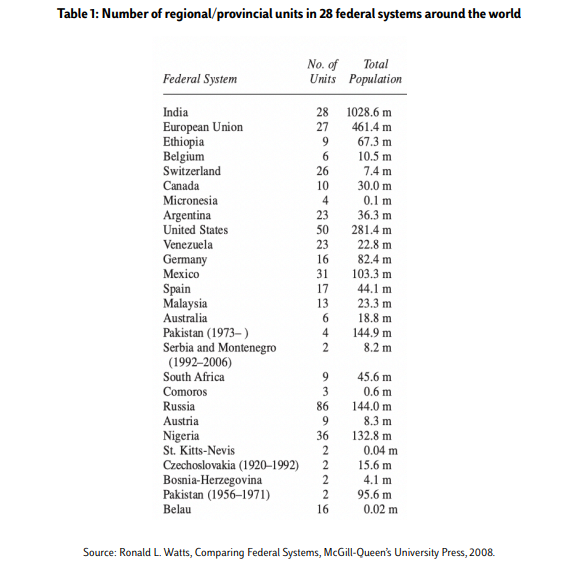

Indeed, experiences from other countries show that when federal systems are composed of only a small number of regional units, this enables regions to challenge the central government and produces politically unstable governance dynamics. Even if we look only at federal systems globally, it is unusual to find federations made up of a very small number of regions. The chart below shows the number of units in 28 federal systems around the world.

An example is Nigeria, which gained independence in 1960 and began as a federation with three colonial-era regions, each dominated by a major ethnic group. This structure deepened political divisions and instability, prompting a redrawing of regional boundaries in 1966 to produce 12 states, eventually growing to 36. Bosnia and Herzegovina, another example of a federation with a small number of constituent “entities” (just 2), continues to experience deep polarization and calls for secessionism. A constitution that sought to end the war by dividing up power has contributed to the “hardening of contentious ethnic identities” as well as instability[6].

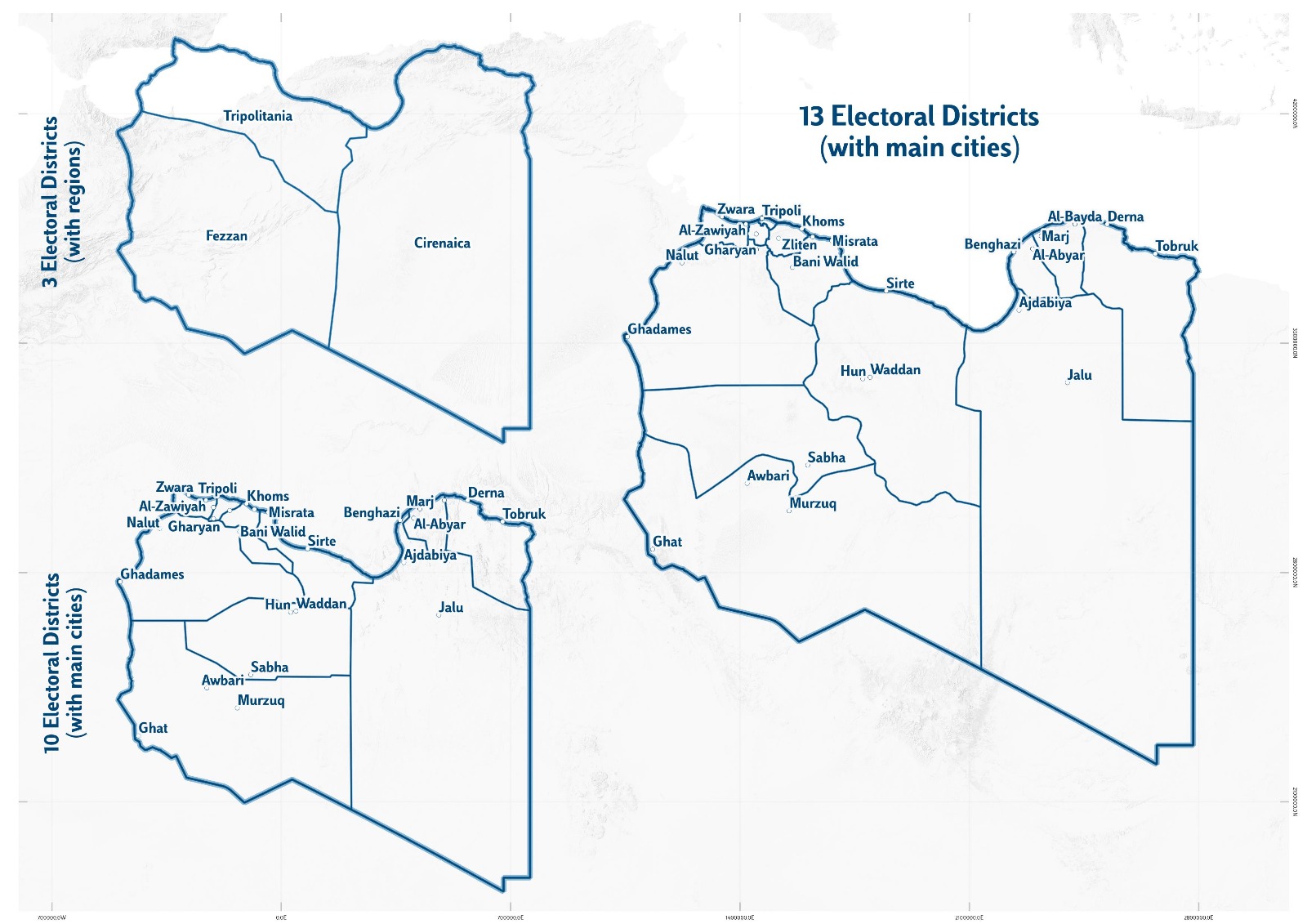

3.3. Using Existing Electoral Districts

Some propose creating 13 governorates or regions based on the existing electoral districts, with the aim of balancing power between regions and the central government, as well as among tribes within each region. However, some parties have objected to using electoral districts as the basis for regional boundaries, arguing that they are purely technical constructs designed for election administration and do not reflect social realities. It has also been noted that some groups would not accept to be incorporated or work with others currently grouped within the same electoral district, should it be turned into a shared governorate or region. As such, using electoral districts as the foundation for drawing new regional or governorate boundaries may lack social legitimacy and could result in grouping together local communities with a history of conflict or without genuine social ties.

In practice, there must be a starting point for rethinking the administrative map. Given the real concerns surrounding the proposal to revive the three historical regions, and the need to avoid geographic concentration of power, the existing electoral districts could serve as an initial starting point from which to begin discussions. However, clear mechanisms must be established to address potential disputes over these boundaries, both at the political and social levels.

4. Organizing the Boundary Delimitation Process

The question of defining the boundaries of local governance units in Libya is a complex and contested one, given the significant economic, cultural, and political weight such boundaries carry. In post-conflict contexts, the involvement of local communities in the boundary-drawing process is considered one of the key factors for successful boundary-making. Boundaries established without social consent often lack community recognition and become a persistent source of disputes. In the Libyan context, marked by regional and tribal divisions, the use of transparent consultative mechanisms is particularly essential. Many of the research participants expressed the view that, given the history of marginalization in many areas and the deep mistrust among actors, any new administrative divisions must be built through a consensual process that includes local communities in decision-making, rather than being imposed from the top down.

In light of the need to enhance the legitimacy and public acceptance of these boundaries—both among institutional actors and citizens—the issue cannot be left to a single ministry or a narrow circle of officials. A well designed process must be put in place to ensure that a wide range of political and social actors are able to contribute their views, rather than having these critical decisions made behind closed doors.

Social acceptance is, of course, not the only factor that should shape administrative boundaries. A number of other factors must be taken into account, including political consensus among key stakeholders, local identities and social ties, historical factors, mobility patterns, economic resources, and infrastructural and administrative capacity to ensure that newly created units are able to manage their own affairs effectively.

4.1. Lessons from Comparative Experiences

One particularly interesting example of a participatory approach to the boundary-setting process is the case of South Africa. Following the end of apartheid in 1991, a political dialogue was launched to draft a new constitution that would lay the foundation for a new system of governance. The initial round of negotiations between the government and the African National Congress (ANC) collapsed in 1992, after the two sides failed to reach agreement on the transitional framework and the majority required to amend the constitution. In March 1993, negotiations resumed, and a new negotiation body was established under the name “Multi-Party Negotiation Process” (MPNP). It included the main political parties (26 in total), along with traditional leaders, representatives of the national government, and regional representatives.

Federalism and the question of regional autonomy emerged as some of the most contentious issues in a highly diverse society marked by deep ethnic, racial, political, and economic divisions, and the legacies of colonialism and apartheid. Some parties, such as the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), strongly pushed for provincial autonomy, and some threatened to use violence if these demands were not met. Other parties, such as the ANC, strongly backed the model of a unitary state with a strong central government.

The issue of regional and municipal boundaries was also particularly sensitive and complex. Under apartheid, South Africa had been divided into “Bantustans” to separate Black and white populations. This division formed a core part of the white-led government’s strategy to create white demographic majorities in certain areas and to deny Black South Africans civil and political rights. After the fall of apartheid, there were calls for a complete overhaul of these boundaries, which had become deeply associated with segregation and discrimination.

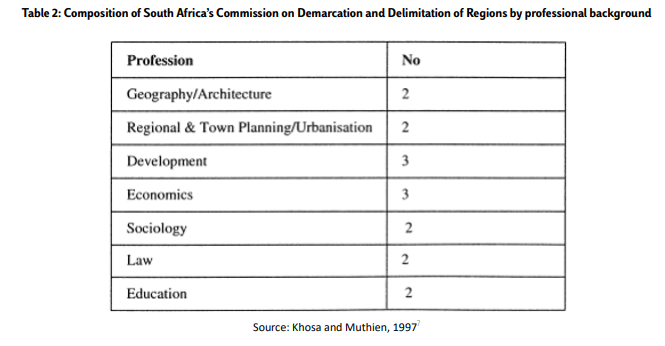

The MPNP established a separate committee dedicated to setting new regional boundaries, called the Commission on Demarcation and Delimitation of Regions (CDDR), composed of experts nominated by the two main parties to the negotiations. This allowed the MPNP and the CDDR to operate in parallel: lead negotiators in the MPNP could focus on drafting the constitution and managing the transitional process, while the CDDR focused exclusively on boundary-related issues. It also enabled the CDDR to concentrate on technical aspects, leaving political considerations to the main negotiation forum, the MPNP. The CDDR was tasked with gathering information, hearing testimonies and proposals, conducting broad consultations, including public hearings, and submitting a report with its findings and recommendations to the MPNP, where political negotiators discussed and made the final decisions on boundaries.

To guide the commission’s work, the MPNP established a set of criteria to be taken into account in drafting boundary proposals. These included: historical boundaries, existing government structures, availability of infrastructure and services, demographic composition, economic viability, development potential, and “cultural and linguistic realities.” The MPNP also instructed the commission to propose boundary options that would minimize financial costs and avoid disruptions to citizens and service delivery.

The CDDR established its own Technical Support Team (TST) and a dedicated administrative and technical secretariat to assist in collecting and providing specialized information on the physical, health, and educational infrastructure of different areas, as well as their demographic, topographic, and environmental features, cultural specificities, transportation networks, and institutional/administrative capacities. It is worth noting that the CDDR did not address the issue of the powers of the regions or provinces. For that purpose, the MPNP formed a separate body—the Technical Committee on Constitutional Issues (TCCI)—tasked with studying and drafting proposals regarding the powers and functions of subnational units.

The table below shows the composition of the boundary delimitation committee by professional background.

At the outset, the boundary committee was granted only six weeks to complete its work, due to the parties’ keenness to conclude the process and proceed with elections. The committee allocated one month for a national consultation and issued a public call for submissions through radio, television, and local, regional, and national newspapers in multiple languages. It sent invitations to political parties, civil society organizations, labor and agricultural unions, state institutions, business associations, women’s organizations, and other groups. A special hearing was held for political parties. In addition, the committee organized oral hearings in five cities and provided simultaneous interpretation into all eleven official languages to ensure broad citizen participation. In some cases, the committee held closed-door sessions without observers or media present to allow delegations to express their views freely, especially in areas where multiple political groups were present and some delegations faced threats of armed violence. Within a single month, the committee received 304 written submissions[8].

At the end of the national consultation, widespread criticism emerged over the limited time available for public input. As a result, the negotiation body extended the committee’s mandate by an additional three months to allow

for broader participation, particularly regarding “sensitive areas” where fears of local conflict over boundaries were high. In total, over the four-month period, the committee received 157 oral submissions and 780 written submissions.

The committee ultimately took six months to complete its work and, in its final report, recommended abolishing the existing four regions and establishing nine new ones[9]. It also proposed granting residents of “sensitive areas”, where boundary tensions were particularly acute, the right to request a public referendum on their regional boundaries[10]. Overall, South Africa’s boundary-setting process is considered a success from a participatory perspective, despite several criticisms. The process highlighted the challenge of balancing the interests of political actors with the input of citizens and civil society, as well as the need to reconcile transparency with confidentiality in final decision. making. It also demonstrated how expert input in the early stages could be effectively combined with political

consensus-building. The process built political buy-in by granting political and social actors the authority to make the final decisions. At the same time, the public consultations broadened participation and allowed for a diversity of local and group perspectives to be included, contributing—at least to some degree—to the emergence of consensus on new boundaries[11].

4.2. Drawing Lessons for Structuring the New Administrative Division Process in Libya

Based on proposals put forward by Libyan stakeholders, an analysis of the Libyan context, and comparative experiences, a framework for organizing the process of defining new administrative boundaries in Libya could be developed along the following lines:

• Establishing a dedicated boundary delimitation committee to draft a proposal for the new administrative boundaries. This committee would be under the authority of the main multi-party negotiating body within the peace process, to clearly link the boundary-setting process with the broader political process. If the negotiating forum is characterized by broad and balanced geographical, political, and social representation, this will be reflected in the work of the boundary committee.

• Expert-based membership: Political and social actors represented within the negotiating forum would nominate experts to serve on the committee. These experts should be non-partisan individuals with relevant technical expertise including in statistics, geography, sociology, economics, public administration, and development. Given the technical complexity of

boundary definition, it is essential to involve experts with the appropriate knowledge and experience.

• Political decision-making: The political and social actors represented within the negotiating forum would make the final decision on the committee’s proposal.

• Social representation: If the negotiating forum is socially inclusive, this will be reflected in both the composition and functioning of the boundary committee. It is crucial that the committee reflect social diversity and facilitate the active participation of local civil society organizations, particularly youth and women’s groups, to ensure that the process is not monopolized by traditional elites or armed groups alone.

• Developing guiding principles for boundary delimitation: The negotiating forum would define a set of clear guiding criteria to direct the committee’s work from its outset. Such criteria would provide a basis for discussing the foundations of the new administrative divisions and help enhance the legitimacy of the proposed boundaries by allowing citizens to

understand the basis on which decisions are made. These criteria could include:

o Historical boundaries

o Topographical features (e.g. mountain ranges, rivers)

o Demographic composition: population size, local identities, and social ties

o Existing government capacity and infrastructure

o Customary land ownership and usage practices (e.g. collective or tribal land)

o Economic potential and development capacity

• Engaging citizens and local communities: Given the sensitivity of boundaries, it is essential to involve citizens and local communities in discussions around the new administrative divisions to gauge the degree of public acceptance of proposals. The boundary committee should organize a national consultation allowing residents across Libya to express their views on the proposed boundaries. Public engagement could be facilitated through the following means:

o Holding public hearings across the country, announced through various channels (radio, television, local newspapers, social media platforms) to ensure widespread awareness

o Presenting maps and proposals to residents in advance of public hearings to enable meaningful feedback

o Inviting relevant stakeholders to submit opinions (political parties, civil society organizations, trade unions, business associations, women’s organizations, tribal leaders, etc.)

o Allowing civil society organizations to attend committee meetings and monitor its proceedings

o Forming subcommittees to conduct in-depth studies of sensitive areas to propose solutions for areas with a high risk of conflict It is important here to discuss the issue of referenda as a tool for citizen participation. Libyan stakeholders have often raised referenda as a potential tool to use to allow citizens to vote on several issues to do with local governance, including regional and municipal boundaries. While referenda provide a space for broad public engagement and for gauging majority opinion, they also carry significant risks, especially in contexts marked by deep divisions and sharp polarization in the aftermath of conflict. In such situations, referenda often exacerbate divisions rather than contribute to consensus-building, national

unity, or enhanced institutional legitimacy.

• Establishing mechanisms for resolving boundary disputes: In the medium and long-term, it is to be expected that disputes over administrative divisions may arise and potentially persist for years or decades after boundaries are established. In light of this, it is important to put in place mechanisms to allow citizens to express concerns about problems arising from the new administrative boundaries and to resolve disputes through peaceful means. For instance, investigation committees could be created to examine disputes, hold consultations with local communities, and submit recommendations to the central government or local authorities. Alternatively, a permanent national body could be established to investigate and resolve boundary-related disputes, particularly if a significant number emerge. For example, Nigeria created a National Boundary Commission in 1987 and granted it the authority to resolve inter-provincial boundary disputes. A permanent boundary body could play a key role in monitoring the emergence of boundary-related tensions and resolving them through various means, while also helping local authorities improve the joint management of cross-boundary resources such as water

Conclusion

Political borders are never ‘natural’—they are constructed through social and political processes and disputes. Administrative boundaries shape the daily lives of residents, determine patterns of exchange, and carry deep symbolic meaning. They reflect historical events and shifts in the distribution of power over time. In Libya, determining the number, boundaries, and powers of local authorities is a complex task that may be addressed either during peace negotiations or in a transitional phase afterward. The central objective of redrawing Libya’s internal geography should be to reduce developmental inequalities between regions and to redistribute resources equitably, thereby building a just and stable system that ensures dignity for citizens and responds to the core demands that triggered the 2011 revolution against the Gaddafi regime.

The proposal outlined in this paper aims to provide a framework for designing a new administrative boundary process in Libya that balances several key considerations: the need for political consensus among the main actors controlling the political process, by granting them the final say on new boundaries and ensuring their acceptance of the process; the meaningful participation of citizens and communities who will be directly affected by the new divisions, empowering them to voice their views and build social consensus; and, finally, the incorporation of technical (economic and administrative) considerations to ensure that the resulting divisions enable local authorities to effectively deliver services and promote equitable development, thereby helping to reduce disparities and strengthen social cohesion and national unity.

References

[1]Intissar Kherigi, “Prospects of Local Governance in Libya: Framing the Debate for Post-Conflict Stability”, Policy Paper, Mediterranean Platform, Luiss School of Government, October 2024

[2]Decree No. 13 of 1963 on the Administrative Organization of the Kingdom.

[3]See for example, GNU Decision no. 182 of 2022, which established 19 provinces to be composed of mayors of the region, headed by an appointed governor; as well as proposals by the Presidential Council in 2022: https://www.albayan.ae/world/arab/2022-11-14-1.4558171.

[4]Kherigi (2024).

[5]“Dabaiba: We proposed the idea of provinces due to problems with the provincial law” (in Arabic), Bawabat Al-Wasat, 5 July 2021

[6]Marie-Joëlle Zahar, “When the Total is less than the Sum of the Parts: The Lessons of Bosnia and Herzegovina”, Forum of Federations, Occasional Paper Series Number 26, 2019

[7]Meshack M. Khosa, M. and Muthien, Y. (1997) ‘The Expert, The Public and The Politician’: Drawing South Africa’s New Provincial Boundaries,’ South African Geographical

Journal, 79:1, pp. 1-12.

[8]Yvonne Muthien and Khosa, M. (1995) ‘The Kingdom, the Volkstaat and the New South Africa’: Drawing South Africa’s New Regional Boundaries, Journal of Southern

African Studies, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 303-322.

[9]In Namibia, by contrast, the boundary committee was given ten months to complete its work.

[10]Sagie Narsiah (2019) ‘The politics of boundaries in South Africa: the case of Matatiele’, South African Geographical Journal, 101:3, pp. 399-414.

[11]Ibid

In Focus

Subnational Governance in Divided Societies: Learning from Yemen to Inform Libya’s Peace Process

MRAD, Mohamed Aziz

8 January 2026

Youth as Catalysts for Shaping Libya’s Future Pathways for Inclusion in National Dialogue and Vision -Making

SKOURI, Abdelkarim

2 December 2025

Hydrogen Valleys and Sustainable Development in Algeria: Pivoting from Hydrocarbons to an Inclusive Euro Mediterranean Hydrogen Economy

STILLE, Leon

21 November 2025